| Home | 1952 | 1953 | 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 | 1960 | 1961 | 1962 | Index |

| . | In the early days of 1957, nobody was expecting this year will mark the beginning of the Space Age. Il was expected that the United States and the Soviet Union, in that order, would launch satellites during the eighteen-month International Geophysical Year, to begin on July 1st, 1957. These first satellites, or ‘moons’ as they were then called, were expected to be launched around 1958. And nobody was expecting that they would have a tremendous impact around the world. |

| Notes: | The letter c place in front of the right colum denotes comments from the author of this site. (v) placed in text refers to the Vocabulary, Definition and Abreviation page. The linked words refer to the Main Entry Index of this site. |

| Content |

| • | January 1957 | "Space for Peaceful Purpose Only" |

| • | February 1957 | Dreaming of Spaceflight |

| • | March 1957 | Cloaked in Secrecy |

| • | April 1957 | Pressure Ahead |

| • | May 1957 | Something Happened in Secret |

| • | June 1957 | They Told Us: They Were Ready! |

| • | July 1957 | IGY: the First Step of the Space Age |

| • | August 1957 | The "Ultimate Weapon" Is Here |

| • | September 1957 | Countdown to a New Era |

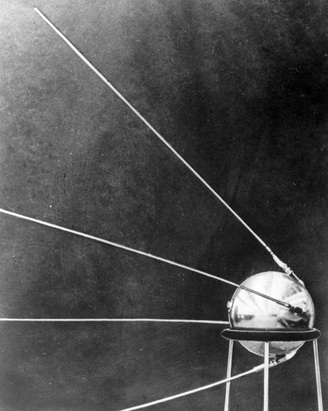

| • | October 1957 | Sputnik |

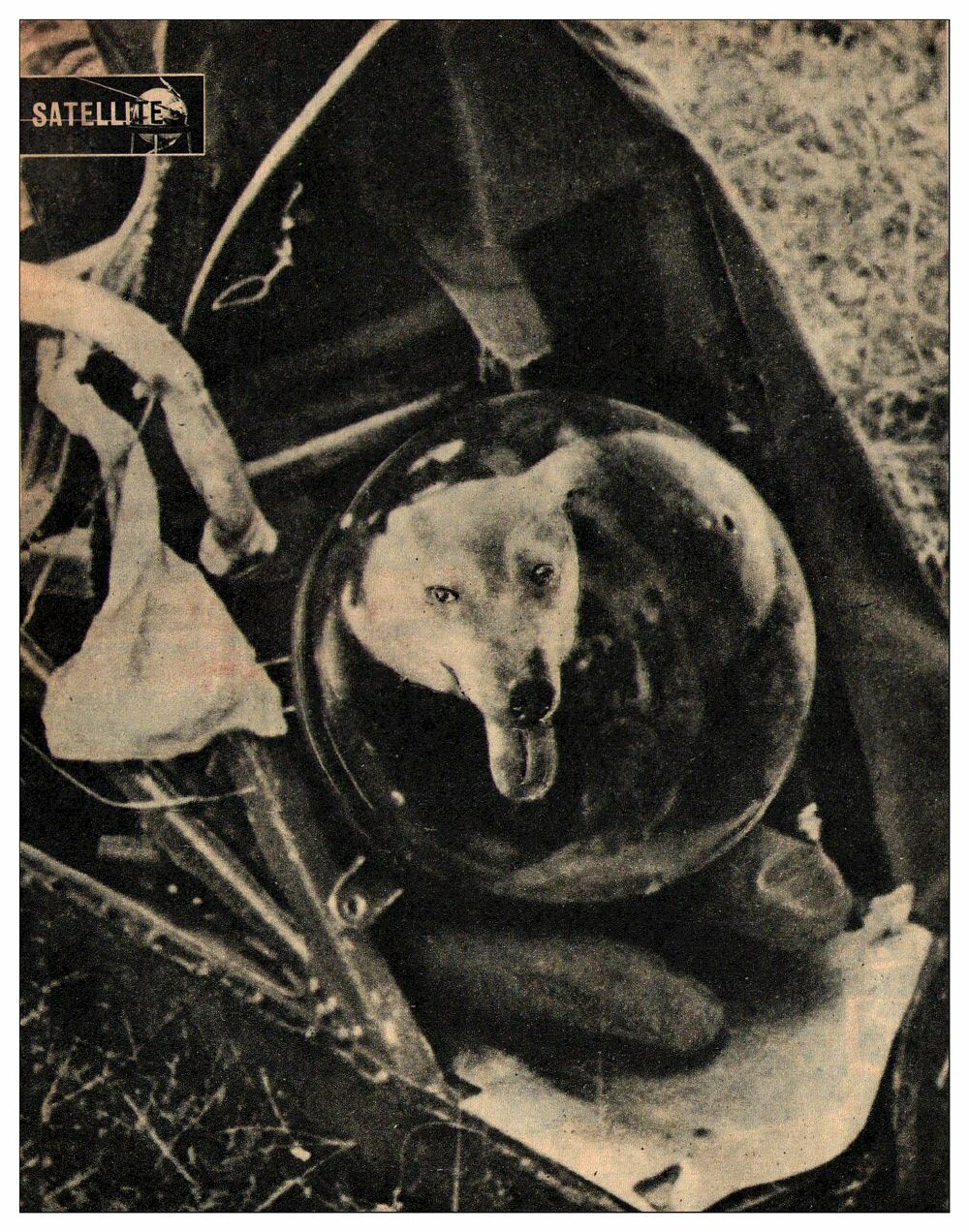

| • | November 1957 | Laika |

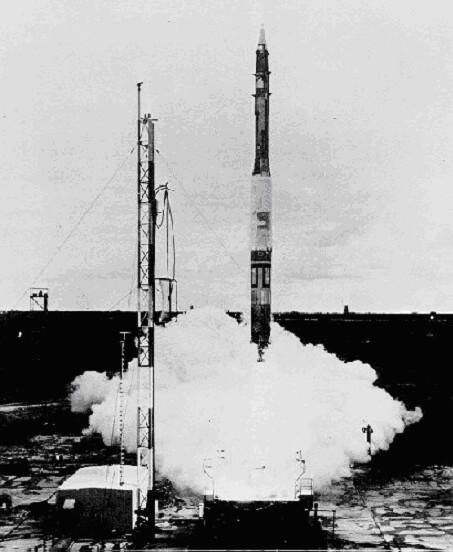

| • | December 1957 | Vanguard |

| • | Annexe A | Missiles and Launchers Summary |

| • | Annexe B | Satellite Summary |

| January: "Space for Peaceful Purpose Only" |

| . | In January, the President of the United States surprised everbody by announcing in his State of the Union Address that he intends to propose banning all military use of space. He then submits to the United Nations a motion: space should be “devoted exclusively to peaceful and scientific purpose.” Such proposal was surprising considering that the U.S. was already developing secret military spy satellites and was thinking of many more military projects. |

|

|

What We Knew Then | What We Now Know | ||||

| U.S. Prepared to Launch Satellites | ||||||

| Tuesday

1 January 1957 |

• | The United States is preparing to launch small Earth satellites under the Vanguard program as part of the International Geophysical Year (IGY), which spans from 1st July 1957 through 31 December 1958. The plan is to send about ten of them at least 300 to 500 kilometers above the Earth’s surface and perhaps 2,500 kilometers into space. These satellites will be basketball-sized spheres of about 50 to 75 centimeters in diameter. It is known that the Soviet Union is also preparing Earth satellites of a similar type. (NYT 11 Jan 57) | ||||

| Korolev to Launch Simple Satellites | ||||||

| Saturday

5 January 1957 |

• | Sergei Korolev asked for permission to Soviet authorities to launch two small satellites, each with a mass of forty to fifty kilograms, during the April-June 1957 period — immediately prior to the beginning of the IGY. Because the United States had plans to launch satellites during this period, Korolev could ensure Soviet pre-eminence by launching one before the start of the IGY. Each satellite would contain a simple shortwave transmitter with a power source sufficient for ten days of operation. (Siddiqi p. 154, Chertok II p. 381 & 382) | ||||

| Eisenhower Asks Controls of Outer Space | ||||||

| Thursday

10 January 1957 |

• | In his State of the Union Message, President

Eisenhower

called for outer space disarmament:

|

||||

| R-7 Test Program and Plesestk as an ICBM Base | ||||||

| Friday

11 January 1957 |

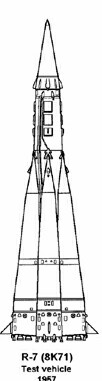

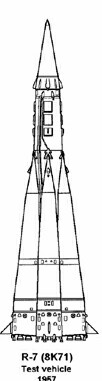

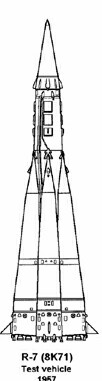

• | Flight test program for the R-7 intercontinental missile approved by decree “On approval of flight-testing program for the R-7 ICBM.” Also, first Soviet ICBM base at Plesetsk authorized by decree “On creation of launch complex Angara at NIIP-53.” (Wade 11 Jan 57) | ||||

| U.S. Proposed Disarmament Plan | ||||||

| Monday

14 January 1957 |

• | The United States presented to the United

Nations a five-point proposal for world disarmament.

It included international control of intercontinental missiles and that

experiments in outer space be “devoted exclusively to peaceful

and scientific purpose.” This proposal again emphasized the necessity for

a working system of inspection and control to eliminate the possibility

of evasion of disarmament pledges. In a new development, however, it suggested

the formation of a special body to undertake this responsibility.

Last November, the Soviet Union had called for a phased reduction of ground troops, a ban on nuclear production for war within two years, immediate suspension of atomic bomb tests, the liquidation of foreign bases and a non-aggression agreement between the North Atlantic Treaty Powers and the members of the Warsaw Pact. (NYT 15 Jan 57) |

||||

|

|

||||||

| Saturday

19 January 1957 |

• | The Soviet Union proceeded to a 500-km altitude nuclear test from Kapustin Yar, using a R-5M missile. (Wade 19 Jan 57) | ||||

|

|

||||||

| Saturday

19 January 1957 |

• | U.S. Army proceeded to a Jupiter A test from Cape Canaveral. The primary objective was to test the accuracy of the guidance system when the missile is fired in a short range trajectory at a high attitude (90 km). The missile closely followed the predicted trajectory which terminated 70 meters beyond and 360 meters to the left of the expected impact point at 114 km range. (Wade 19 Jan 57) | ||||

| Sputnik 1 Design Approved | ||||||

| Friday

25 January 1957 |

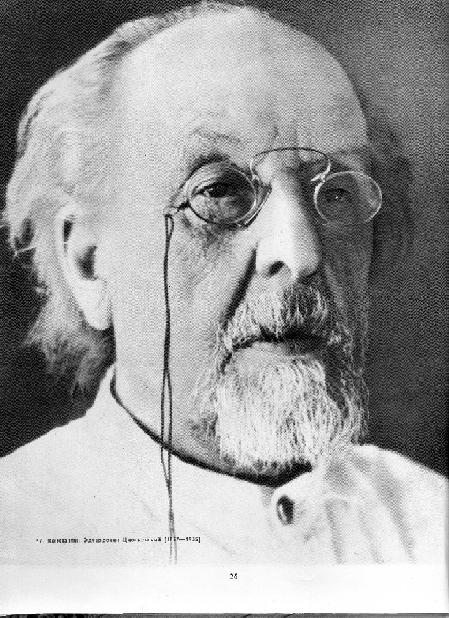

• | Sergei Korolev approved the initial design details of the first satellite, officially designated Simple Satellite No. 1 (PS-1). (Siddiqi p. 155) | ||||

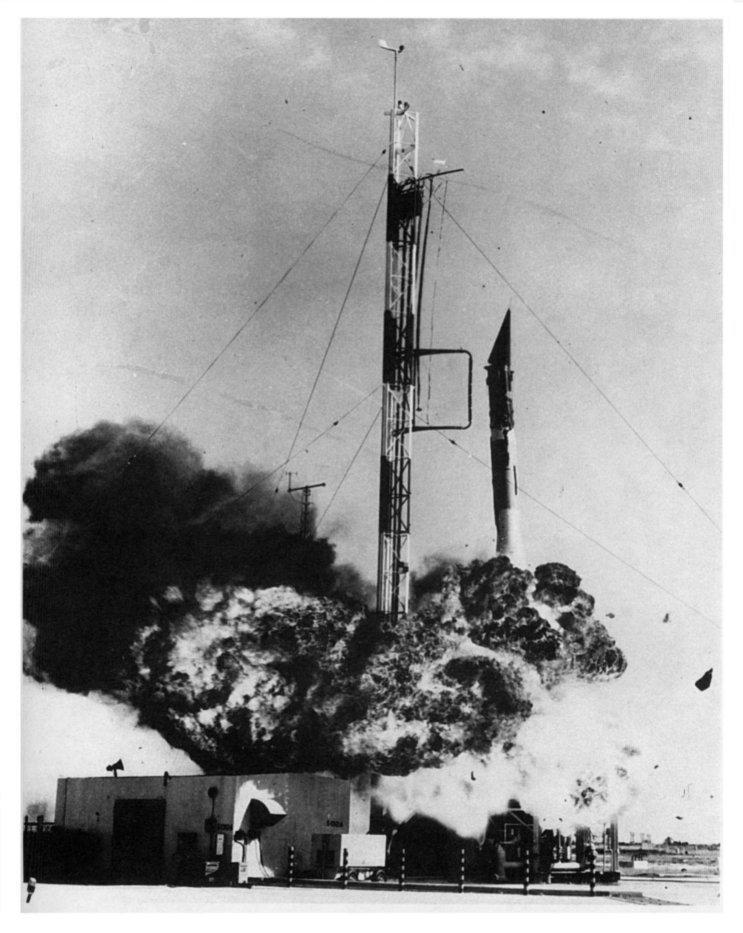

| Air Force Rocket Failed Test | First Thor Missile Test | |||||

| Saturday

26 January 1957 |

• | An Air Force attempt to launch a test version of its Thor ballistic missile was reported to have ended in failure, with the multi-ton rocket in wreckage. (NYT 27 Jan 57, A&A 1915-60 p. 85) | • | First attempted test flight of USAF Thor IRBM, only 13 months after first production contracts were signed. The missile failed at lift-off. Following liquid oxygen contamination, a valve failed, thrust decayed and the booster settled back through the thrust ring, causing an oxygen fire, followed by booster explosion. (Wade 26 Jan 57) | ||

| Designing a Space Capsule | ||||||

| Junuary 1957 | • | The NACA Ames group reported its conclusions on a new rocket-powered

vehicle for "efficient hypersonic flight," featuring a flat-top, round-bottom

configuration. Interestingly enough, the document contained as an appendix

a minority report recommending that a nonlifting spherical capsule

be considered for global flight before a glide rocket. "The appendix was

widely read and discussed at Langley at the time" recalled Hartley Soulé,

a Langley senior engineer, "but there was little interest expressed in

work on the proposal."

NACA study groups continued their investigations of manned glide rocket concepts through the spring and summer 1957. (Mercury O p. 71) |

| February: Dreaming of Spaceflight |

| . | While the Americans were developing their satellite launcher (Vanguard) and the Soviet their R-7 (in absolute secrecy), the public was already dreaming of space travel. At the first National Symposium on Astronautics, the interest was not when will the first satellite be launched, but: when would we explore the Moon? For their part, U.S. military planners were thinking that space will someday become a battlefield: “Our safety as a nation may depend on our achieving ‘space superiority,’” they claimed. | ||

| Date | What We Knew Then | What We Now Know | ||

| Vanguard TV-1 Slipped | ||||

| Early

February 1957 |

• | At Cape Canaveral, one of the main event of January and February was the arrival of the second Vanguard test vehicle (TV-1). Although the difficulties encountered during the prelaunch procedures were comparatively minor, their correction ate up precious time. Hopes for a February flight vanished rapidly. (Vanguard p. 175-6) | ||

| “Man Could Fly to Moon by 1982” | Much Sooner than Expected | |||

| Thursday

7 February 1957 |

• | According to Dr. Clifford Furnas, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Development, “If you really want to do it, and make the effort, an unmanned rocket could be launched in ten years that would circumnavigate the Moon and return to Earth. A manned rocket to the Moon could be developed and fired in about twenty-five years.” He made it clear that no specific projects for space travel to the Moon was under way within the Defense Department. But with advancing rocket technology and lots of money, he said, such a trip would be possible. | c | In fact, the first robotic lunar flights happened only 2 years later (1959, Luna) and the first manned expedition to the Moon 11 years later (1968, Apollo 8). -C.L. |

| Dr. Furnas said the Soviet was probably closing the technological gap on the United States, but they are “still a long way behind.” The United States can “speak with confidence” about its technological lead, he sais, “but can’t be complacent.” (NYT 8 Feb 57) | c | In fact, the Soviets were already ahead of the Americans, and by far, as we will see again and again in the upcoming months. -C.L. | ||

| Preparing for Dyna Soar | ||||

| Monday

14 February 1957 |

• | NACA established "Round Three" Steering Committee to study feasiblity of a hypersonic boost-glide research airplane. "Round Three" was considered as the third major flight research program which started with the X-series of rocket-propelled supersonic research airplanes, and which considered the X-15 research airplane as the second major program. The boost-glide program eventually became known as Dyna Soar. (Wade 14 Feb 57) | ||

| Sputnik To Be Launched in April-May | ||||

| Tuesday

15 February 1957 |

• | The USSR Council of Ministers formally signed a decree titled "On Measures to Carry out in the International Geophysical Year," stipulating that two new satellites, PS-1 and PS-2, weighing approximately 100 kilograms, could be launched in April-May 1957. It was proposed that two R-7 rockets from those prepared for the flight-design testing program be used for the launch. However, the launch of the simplest satellite would not be permitted until after one or two successful R-7 rocket tests. Meanwhile, the Object D launch was pushed back to April 1958. (Siddiqi p. 155, Chertok II p. 382) | ||

| Piloted Spaceflight Near | Good Estimates | |||

| Monday

18 February 1957 |

• | At the 3-day first National Symposium on Astronautics, the consensus was that while technical problems put the first space voyage by humans many years away, this achievement was certain enough to warrant concentrating practical research. “We believe that flight outside the atmosphere is now a reality,” said Brig. Gen. H. F. Gregory, commander of the Air Force Office of Scientific Research. According to Krafft Ehricke, Convair scientists, to put a four-man space ship in an orbit above the Earth would cost at least $350 millions and would entail the work of 7,000 people for five years. (NYT 19 Feb 57) | c | These estimates were nor far from reality. First piloted spaceflights took place four years later and Ehricke estimates were close to Mercury project costs, manpowers and duration. -C.L. |

| Officer Predicts Battles In Space | Battlefield, no. Prestige, yes. | |||

| Tuesday

19 February 1957 |

• | “Several decades from now, the important battles may not be sea battles or air battles, but space battles,” declared Maj. Gen. Bernard Schriever, commander of the Air Force’s Western Development Division. “In the long haul,” he continued, “our safety as a nation may depend on our achieving ‘space superiority.’ We should be spending a certain fraction of our national resources to insure that we do not lag in obtaining space supremacy.” General Schriever suggested that in respect to the future use of ballistic missiles, man-made satellites and space vehicles, “we are somewhat in the same position today as were military planners at the close of the first World War when they were trying to anticipate the employment of aircraft in future wars.” He added that “Besides the direct military importance of space, our prestige as world leaders might well dictate that we undertake lunar expeditions and even interplanetary flight when the appropriate technological advances have been made and the time is right.” (NYT 20 Feb 57) | c | Fortunately for us, space did not became a battlefield, althougth very important for military surveillance. However, Gen. Shriever was right when he considers that prestige would "dictate" U.S. to undertake lunar and planetary missions. -C.L. |

| U.S. IGY Program | ||||

| Sunday

20 February 1957 |

• | U.S. National Committee for the IGYsubmitted a report at the Technical Panel on the Earth Satellite Program to the National Science Foundation and the Department of Defense which outlined a post-IGY space research program. (A&A 1915-60 p. 85) | ||

| To the Moon, and Then to Mars | Good Strategy | |||

| Friday

23 February 1957 |

• | Space flights to the Moon and Mars may come within twenty years, as was discussed this week as the first National Symposium on Astronautics. it was the consensus that, since the Moon is the closest heavenly body, it is bound to be the initial stepping stone out into space. First unmanned vehicles will be sent to and around the Moon. Then manned flights presumably will follow, with landings on the Moon if conditions there prove feasible. The next step, according to current thinking, would be forays at Mars, the next closest heavenly body. (NYT 24 Feb 57) | c | This "thinking" was about right: we went to the Moon in the 1960s, and than proceed to Mars (by robotic probes only). -C.L. |

| ‘We’ll Never Land on the Moon’ | Rignt and Wrong | |||

| Friday

23 February 1957 |

• | Dr. Lee De Forest, inventor of the vacuum tube, predicted that man would never reach the Moon “regardless of all future scientific advances.” He also said that trans-ocean television “is only a matter of ten years or less.” (NYT 24 Feb 57) | c | Sometime, experts are right, sometime they are wrong. Of course, we landed on the Moon in 1969. Trans-oceanic television became a reality in 5 to 8 years (first with Relay and Syncom experiments in 1963, and than with Intelsat in 1965). -C.L. |

| 16,000 G Survival ! | ||||

| February 1957 | A chimpanzee rocketed down the track 1.5-kilometer long, braked to a stop, and survived a load of some 247 G for a millisecond, with a rate of onset of 16,000 G per second. (Mercury O p. 40) |

| March: Cloaked in Secrecy |

| . | During March, many space projects progress in secret. For instance, a magazine revealed that the Pentagon was preparing to send space probes to the Moon. While the Soviets reported training dogs for spaceflight, they kept secret the fact that their first R-7 missile arrived at the top-secret launch site (the future Baikonur Cosmodrome). For its part, the U.S. Air Force was studying a missile’s early warning satellite system… “Space for peaceful purpose only,” as they said. | ||

| Date | What We Knew Then | What We Now Know | ||

| Mishap Reported In Missile Test | Jupiter Failed in Flight | |||

| Friday

1 March 1957 |

• | A Defense Department spokesman said that "something went wrong" when a guided missile was fired in a test at Patrick Air Force Base in Florida. (NYT 2 Mar 57) | • | Test flight of a Jupiter

IRBM missile from Cape Canaveral. The missile achieved an altitude of 14

kilometers. Flight terminated after 7.4 seconds because of missile break-up.

Failure was attributed to overheating in the tail section. (Wade

1 Mar 57)

The Jupiter A launched on March 1, 1957. (NASA) |

| Vanguard Progress | ||||

| Saturday

2 March 1957 |

• | Dr. Hugh Nodishaw, executive secretary of the U.S. Committee for iGY research program, stated that progress on Project Vanguard was satisfactory but that there are still some doubt as to the date when the first satellite would be ready to launch. He added that the rocket first-stage engine’s test performance had exceeded expectations. (NYT 3 Mar 57) | ||

| USAF Preparing Moon Probe | Secrets Revealed | |||

| Saturday

2 March 1957 |

• | Brig. Gen. H. F. Gregory, director of the Air Force’s Office of Scientific Research, said USAF may shoot a rocket around the Moon within five years. He confirmed an article in Missiles and Rockets magazine that quoted him as saying: “Several Moon rocket study contracts are in the works and it is imperative that we carry out these scientific research projects to stay ahead of the Russians. When I say that we will have a Moon rocket in less than five years, it is a conservative estimate.” | c | "A Moon rocket in less than five years" was indeed a conservative estimate since the first USAF Pioneer lunar probes was be launched a 1½ year later. |

| Erik Bergaust, the magazine’s managing editor, said that according to some of U.S.’s leading rocket engineers, three different Moon rocket projects would be attempted within the next few years, the first of them possibility as early as 1959. (NYT 3 Mar 57) | c | Bergaust had good contacts since both the U.S. Army and the U. Air Force were developing in secret lunar probes that would be launched by the end of 1958. -C.L. | ||

|

|

||||

| Sunday

3 March 1957 |

• | The first flight-ready R-7 missile arrived at the firing range on 3 March, with its full complement of five boosters. On March 4, Sergei Korolev signed the Technical Assignment No. 1 document, formally approving preparations for the R-7 launch. (Chertok II p. 334, Siddiqi p. 157) | ||

| Jupiter Missile Test | ||||

| Thursday

14 March 1957 |

• | Successful Jupiter A missile test flight from Cape Canaveral. Actual range was 256 kilometers, 4 kilometers under and 1.25 kilometer left of the intended impact point. (Wade 14 Mar 57) | ||

| NERVA Research Slowed | ||||

| Monday

18 March 1957 |

• | Under guidance from the Secretary of Defense, the Atomic Energy Commission reduced its program on nuclear rocket propulsion to a single laboratory effort, phasing out work at the University of California’s Radiation Laboratory and concentrating AEC development efforts at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. (Wade 18 Mar 57) | ||

| Soviet Prepared Dogs for Space | ||||

| Sunday

24 March 1957 |

• |

|

||

| Another Jupiter Test | ||||

| Thursday

28 March 1957 |

• | A Jupiter A test flight from Cape Canaveral was successful with impact point at 220 meters short and 320 meters to the right. (Wade 28 Mar 57) | ||

| USAF Early Warning Satellite | ||||

| During March | • | Feasibility research study instituted by U.S. Air Force on the Midas early warning satellite. (A&A 1915-60 p. 85) |

| April: Pressure Ahead |

| . | In April, we could already feel some of the pressure that will be put on space activities. For instance, the U.S. Navy commander in charge of launching the first Vanguard satellite hope to do it in secret. For its part, Soviet Communist party leader Nikita Khrushchev required that the first intercontinental ballistic missile be launched before the May 1st Labor Celebrations. Otherwise, an astonishing incident happened: an American missile was destroyed erroneously in flight. | ||

| Date | What We Knew Then | What We Now Know | ||

| Newsmen Barred From Launch? | ||||

| Friday

5 April 1957 |

• | Rear Admiral Rawson Bennett, chief of U.S. Navy research in charge of launching the first Vanguard satellite, said he planned to keep the event secret until the satellite was orbiting the Earth. He had decided to make no advance announcement and to prevent newsmen from witnessing the launching. In his view, with the press and the nation focusing on this effort, those in charge might succumb to a “very human temptation” to launch the vehicle despite less-than-ideal circumstances. He stressed that this was his decision, adding: “I might be overruled.” Other officials predicted this position would be overcome on the ground that the Vanguard project had been specified by President Eisenhower to be a scientific venture outside the domain of military secrecy. (NYT 6 Apr 57, 7 Apr 57) | ||

| First Satellite Launch in 1958? | ||||

| Saturday

6 April 1957 |

• | According to Gilman Reid Jr., head of the

satellite project office in the National Academy of Sciences, the first

50-centimeter Vanguard satellite

probably will be launched early next year. When Project Vanguard was first

announced, in July 1955, scientists had hoped it would be possible to fire

at least one test satellite before the geophysical year began. Mr. Reid

said it now appeared that it would be another nine to twelve months before

the first satellite could be launched.

On his part, Murray Snyder, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs, indicated that the press would be allowed to cover the satellite launching. Present plans call for at least six satellites to be launched during the geophysical year. Five major experiments have been planned so far for the individual satellite. If the first firings prove successful, the satellite experimental program is likely to be broadened. (NYT 7 Apr 57) |

||

| R-7 To Fly Before May 1st | ||||

| Wednesday

10 April 1957 |

• | At the meeting of the Central Committee, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev announced the requirement to perform the first R-7 ICBM missile launch before 1 May as a gift in honor of the Labor holiday. General Aleskey Nesterenko, chief of the launch site, vehemently protested, showing that it would not be possible to prepare the firing range, launch complex and the missile itself in the 20 days remaining. (Chertok II p. 346) | ||

| Vanguard Instruments Tested | Science Instruments Tested | |||

| Thursday

11 April 1957 |

• | A Navy rocket climbs 203 kilometers, carrying Vanguard science instruments, which received their first aerial test. (NYT 12 Apr 57) | • | U.S. IGY scientific satellite equipments, including a radio transmitter and instruments for measuring temperature, pressure, cosmic rays and meteoroid dust encounters, was tested above Earth for the first time, as an Aerobee Hi rocket containing this equipment was fired by the Navy to a 203-kilometer altitude. (A&A 1915-60 p. 85, Wade 11 Apr 57) |

| Navy Prepared 2nd Vanguard | ||||

| Thursday

11 April 1957 |

• | The U.S. Navy is preparing for the second test firing of the Vanguard rocket that will hurl a satellite into space. (NYT 12 Apr 57) | ||

| Rocket Engine Defective | ||||

| Saturday

13 April 1957 |

• | The U.S. Navy reports that the first engine produced for the Vanguard rocket has been rejected because of technical defects, but schedule stands. (NYT 14 Apr 57) | ||

| Delays in Vanguard Firing | ||||

| Tuesday-Thursday

16-18 April 1957 |

• | The Vanguard rocket test firing was postponed many times following technical problems. (NYT 17 Apr 57, 18 Apr 57, 19 Apr 57) | ||

| Vanguard Rocket Engine Tested | ||||

| Friday

19 April 1957 |

• | U.S. Navy succeed in static firing the 1st stage engine of the second Vanguard rocket. (NYT 20 Apr 57) | ||

| A Thor Missile Destroyed… | … by Mistake! | |||

| Saturday

20 April 1957 |

• | A Thor missile, launched from Cape Canaveral, was destroyed by range safety officer. (A&A 1915-60 p. 86) | • | The Thor IRBM missile was destroyed by mistake. The missile was actually on course throughout its flight, but the console wiring error led the range safety officer to believe it was headed inland rather than out at sea, so he hit the destruct button. (Wade 20 Apr 57) |

| Origins of Vandenberg AFB | ||||

| Tuesday

23 April 1957 |

• | Vandenberg Air Force Base is established on 250 square kilometers of what was then Camp Cooke. (Wade 23 Apr 57) | ||

| U.S. Offers To Ban Space Missiles | ||||

| Thursday

25 April 1957 |

• | The United States indicated today its willingness to include a ban on outer space guided missiles in a first step toward an international disarmament agreement. (NYT 26 Apr 57) | ||

| A Jupiter Missile Test | ||||

| Friday

26 April 1957 |

• | A Jupiter IRBM, fired from Cape Canaveral to test the design version of the airframe and rocket engine, terminated at 93 seconds because of propellant slosh. The missile achieved an altitude of 18 kilometrers. The flight was partially successful. (Wade 26 Apr 57) | ||

| USAF Hypersonic Weapons | ||||

| Tuesday

30 April 1957 |

• | U.S. Air Force headquarters directed the Air Research and Development Command to formulate a development plan encompassing all hypersonic weapon systems (Dynasoar, Hywards, Bomi, Brass Bell, Robo). (Wade 30 Apr 57) | ||

| Aerobee Record Flight | ||||

| Tuesday

30 April 1957 |

• | An Aerobee-Hi sounding rocket, fired fron White Sands, reached speed of 7,900 km/hr and an altitude of 311 kilometers. (NYT 1 May 57, A&A 1915-60 p. 86) | ||

| The ‘Van Allen Team' | An Important Spacemen | |||

| During April 1957 | • | The Upper Atmosphere Rocket Research Panel was renamed the Rocket and Satellite Research Panel. Its chairman is James A. Van Allen of the State University of Iowa. (A&A 1915-60 p. 86) | c | James Van Allen will play key roles in space activities, first as a scientist making an important discovery (the Van Allen radiation belts) and as a critic of piloted spaceflight. -C.L. |

| Origins of the Saturn 1 Booster | ||||

| During April 1957 | • | The U.S. Army Ballistic Missile Agency, at Redstone Arsenal, Ala., began studies of a large clustered-engine booster to generate 680 tons (1.5 million pounds) of thrust, as one of a related group of space vehicles. (Apollo C1 1957) |

| May: Something Happened in Secret |

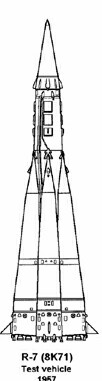

| . | A crucial step in military weapons and space exploration was taken this month: the Soviet Union launched the first-ever missile able to deliver nuclear warhead anywhere in the globe. This R-7 Intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) will become the most usefull space launcher: the Semiorka that launched thousands of spacecraft. But since the first R-7 trial ended in failure, it was kept secret for decades. Also in May, the United States successfully tested its second Vanguard rocket. | ||

| Date | What We Knew Then | What We Now Know | ||||

|

|

||||||

| Wednesday

1 May 1957 |

• |

|

• | At 1:29 Eastern time, the second Vanguard test vehicle (TV-1) lifted off. The two-stage vehicle roared to an altitude of 195 kilometers. Its first stage was the last of the Viking research rockets slightly modified for Vanguard purposes. The second stage was a prototype of the solid-propellant rocket destined to become the third stage of the finished Vanguard vehicle. The primary purpose of the launch was to flight-test the third-stage prototype for spin-up, separation, ignition, and propulsion and trajectory performance. A secondary objective was to further evaluate ground handling procedures, techniques and equipment, and the in-flight vehicle instrumentation and equipment. All objectives were met. (Vanguard p. 175-6) | ||

| Dress Rehearsal for R-7 | ||||||

| Saturday

4 May 1957 |

• | At Baikonur Cosmodrome, technicians carried out a complete dress rehearsal of a R-7 missile transportation from the Assembly-Testing Building (MIK) to the launch pad. At the pad, the missile was up-righted and held down by the pad's four "petals." After installation, engineers established electrical and pneumatic connections with ground equipment. The entire rehearsal was uneventful. (Siddiqi p. 157) | ||||

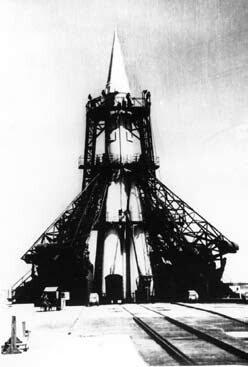

| Traditions Established | ||||||

| Monday

6 May 1957 |

• | The first R-7

missile was moved once again to the pad. At 7 a.m., in keeping with a tradition

religiously observed to this day, a diesel engine rolled the erector platform

through the wide MIK gates. Carrying the booster, it crept along the rail

line to the launch site.

A R-7 roll-out (not the first one). On that day, a tradition was established: the State Commission chairman, the chief designers, the firing range chief of control, and anybody who wanted to, would come to the solemn ceremony to see the latest missile hauled out of the MIK. (Siddiqi p. 157, Chertok II p. 344) |

||||

| Holaday Named Missile Czar | ||||||

| Monday

6 May 1957 |

• | William Holaday was named as Special Assistant for Guided Missiles, Department of Defense. (A&A 1915-60 p. 86, NYT 14 May 57) | ||||

| R-7 To Be Launched in Mid-May | ||||||

| Wednesday

8 May 1957 |

• | The Soviet State Commission formally met to set the first R-7 launch window between May 13 and 18. (Siddiqi p. 157) | ||||

| Vandenberg Breaking Ground | ||||||

| Thursday

9 May 1957 |

• | At Lompoc, 270 kilometers Northwest of Los Angeles, the Air Force broke ground for a $100 millions facility where units will be trained to handle Atlas and Titan intercontinental missiles and Thor intermediate-range missiles under development. The facility will occupy 250 square kilometers of the former Camp Cooke, where armored and infantry units were trained during World War II and Korea. (NYT 10 May 57) | ||||

| R-7 Launch Scheduled | ||||||

| Tuesday

14 May 195 |

• | The State Commission met during the night to approve the first R-7 launch between 14:00 and 17:00, Moscow Time, the following day. There were several reasons for the time slot selection. The launch time had to be during daylight hours for local optical tracking. The re-entry over Kamchatka peninsula of the dummy warhead had to be observed in the night sky. Finally, the launch had to occur as close to night-time as possible so as to prevent observation by U.S. optical tracking stations. Fuelling began at 4:00, Moscow Time, on 15 May. (Siddiqi p. 157-8) | ||||

| First Launch of a Semiorka | ||||||

| Wednesday

15 May 1957 |

• |  At

21:00, local time (19;00, Moscow Time), the first R-7

intercontinental ballistic missile was tested. But, right on the launch

pad, a fire started in the aft compartment of the Block D strap-on booster.

It was amazing that the missile was able to fly for another 100 seconds.*

Controlled flight lasted for 98 seconds. Then, thrust of the engine in

Block D dropped abruptly and the booster separated. The remaining four

boosters were running and the control system was trying to restrain the

missile. The control surfaces could not cope with the disturbance. They

were at their limit and, at 103 seconds, the command passed validly. It

had been so close to separation. There were no glitches in the core booster;

if it had held out for another 5 to 10 seconds, the command for separation

would have passed, and then the second stage, having gained its freedom,

could have continued the flight. For the engineer, the launch system had

passed the test since, after all, the booster cluster had flown for 100

seconds. (Siddiqi p. 158-9,

Chertok

II p. 352 & 355). At

21:00, local time (19;00, Moscow Time), the first R-7

intercontinental ballistic missile was tested. But, right on the launch

pad, a fire started in the aft compartment of the Block D strap-on booster.

It was amazing that the missile was able to fly for another 100 seconds.*

Controlled flight lasted for 98 seconds. Then, thrust of the engine in

Block D dropped abruptly and the booster separated. The remaining four

boosters were running and the control system was trying to restrain the

missile. The control surfaces could not cope with the disturbance. They

were at their limit and, at 103 seconds, the command passed validly. It

had been so close to separation. There were no glitches in the core booster;

if it had held out for another 5 to 10 seconds, the command for separation

would have passed, and then the second stage, having gained its freedom,

could have continued the flight. For the engineer, the launch system had

passed the test since, after all, the booster cluster had flown for 100

seconds. (Siddiqi p. 158-9,

Chertok

II p. 352 & 355). |

||||

| c |

|

|||||

| Long-distance Jupiter C Test | ||||||

| Wednesday

15 May 1957 |

• | The second Jupiter C three-stage re-entry missile was launched from Cape Canaveral to test the thermal behavior of a scaled-down version of the Jupiter nose cone during re-entry. The composite missile consisted of three stages: the first stage was an elongated Redstone using alcohol and liquid oxygen as propellant, and the second and third stages were made up of clusters of 11 and 3 scaled-down Sergeant solid propellant rockets, respectively. The separated nose cone should have reached a nominal range of 1,950 kilometers. The missile began to pitch up at 134 seconds, and impact was 777 kilometers short of the intended impact point. The nose cone was not recovered; however, instrument contact with the nose cone through re-entry indicated that the ablative-type heat protection for warheads was successful. (Wade 15 May 57) | ||||

| A Dog at 212 km | ||||||

| Thursday

16 May 1957 |

• | The first operational R-2A missile launch carried dogs up to 212 km. (Wade 16 May 57) | ||||

| Vanguard Satellite Delayed | ||||||

| Sunday

19 May 57 |

• | The first 10-kg Vanguard

satellite will not be launched this September, as hoped. Probably the launch

will be delayed at least until the spring of 1958. The difficulties have

come not only in designing and building the three-stage rocket but also

in the scientific equipment to track the satellite on its journey. Dr.

Richard W. Porter, chairman of the technical panel of the satellite program,

disclosed that all twelve camera tracking stations necessary to fix the

position of the satellite accurately will not be operating until April

1958.

Before attempting to launch a satellite, the Navy plans to make six tests firings of various parts of the rocket. During these tests, it is possible that an unintentional satellite will be placed in orbit. Dr. Porter raised this possibility that the third-stage of the rocket, which in the actual firing will contain the satellite, will “continue to float in the orbit as an inert object” after burning out. (NYT 20 May 57) |

||||

| Vanguard Unveiled | ||||||

| Tuesday

28 May 1957 |

• | The first full-scale model of the Vanguard

rocket that will launch an Earth satellite has been completed. It will

be test-fired soon. The Navy also has completed the first instrumental

model of the satellite. These developments were disclosed today as the

Navy stripped away some of the secrecy surrounding the Vanguard program

that projected at least six Earth satellites into space during the forthcoming

International Geophysical Year. For the first time, reporters and

photographers were permitted to observe the rockets under construction

at the Glenn L. Martin Company plant north of Baltimore.

One of the rockets now is being readied for shipment to Patrick Air Force Base in Florida, where it is expected to be test-fired sometimes around the start of the geophysical year. The purpose of the trial will be to test the effectiveness of the first stage. Navy officials still would not commit to a firm schedule for the attempted launching of the first satellite. Rear Admiral Rawson Bennett, chief of the Office of Naval Research told, however, that his “idea” is that the attempts “very likely” would come around March 1958. (NYT 29 May 57) |

||||

| Vanguard in Trouble | ||||||

| End of May |

Second stage of Vanguard being hoisted into position. |

• | Less than a month after Vanguard TV-1, the members of the Vanguard Operations Group were telling themselves that Project Vanguard had become Project Impossible. Getting the project's third test vehicle, TV-2, out of the Martin plant, down to the field, onto the launch stand, and up in the air was an ordeal of more than five months' duration. So many troubles beset the process that at one point Dan Mazur, project director, would have resigned in disgust had it not been for the gentle-spoken persuasiveness of project director Hagen. (Vanguard p. 176-7) | |||

| Jupiter Flew Up to Its Limits | First Successful Flight For Jupiter | |||||

| Friday

31 May 1957 |

• | A U.S. Army Jupiter IRBM was fired 2,400 kilometers, limit of its designed range, and to an altitude of 400-500 km, the first successful launching of an IRBM. (A&A 1915-60 p. 86) | • | The Jupiter missile was fired from Cape Canaveral to test the range capability and performance of rocket engine and control system. Although the missile was 469 kilometers short of its estimated 2,500 kilometers impact point, this was the first successful flight of the Jupiter. All phases of the test were successful during this first firing of the IRBM in the western world. (Wade 31 May 57) |

| June: They Told Us, They Were Ready! |

| . | Four months before launching the first man-made satellite, the Soviet Union advertized it was nearly ready to do so. But nobody took notice. Also during June, both Soviets and Americans tried their brand new intercontinental ballistic missiles. And maybe, it was reported, we had found vegetation on Mars! | ||

| Date | What We Knew Then | What We Now Know | ||

| Soviet Ready to Launch a Satellite | ||||

| Saturday

1 June 1957 |

• | The Soviet Union announced that it had completed work on the rockets and instruments necessary to launch its first Earth satellite. In an article publish in Pravda, Prof. Alexander Nesmeyanov, president of the Soviet Academy of Science, said Soviet scientists “have created the rockets and all the instruments and equipment necessary to solve the problems of the artificial Earth satellite.” The article gave no date for the launch; preparations have aimed, however, at a target date sometime within the International Geophysical Year starting July 1. (NYT 2 Jun 57) | ||

| High-altitude Record Flight | ||||

| Sunday

2 June 1957 |

• | U.S. Air Force Captain Joseph Kittinger, Jr. remained aloft in plastic Man High I balloon over Minnesota for 8 hours 54 minutes, being above 28 kilometers for 2 hours and reaching 29.2 kilometers maximum altitude. This was the first solo balloon flight into the stratosphere. (A&A 1915-60 p. 86) | • | Captain Joseph Kittinger stayed aloft inside his sealed gondola for nearly seven hours, breathing pure oxygen, making visual observations, and talking frequently with John Stapp, the flight surgeon, and other physicians on the ground. Kittinger spent two hours above 28 kilometers; his maximum altitude during the flight was 29 kilometers. (Mercury O p. 51) |

| Vanguard in Trouble | ||||

| Early June 1957 | • | With the arrival of Vanguard TV-2 at Cape Canaveral, in early June, new troubles presented themselves. Profound groans and profane gripes filled the Vanguard hangar as inspection revealed that both the first-stage tankage and engine contained fine filings, metal chips and dirt. The Vanguard crewmen could clean the tankage, but getting the dirt out of the engine was beyond their capacities. (Vanguard p. 178) | ||

| A Second R-7 Prepared | ||||

| Wednesday

5 June 1957 |

• | The second R-7 missile was delivered to the launch site, after a new heat-deflecting shields had been installed in the tail section of the missile. Preparation and testing went considerably faster than with the first one, and five days later, the missile had already been fuelled and was ready for launch. (Chertok II p. 358, Siddiqi p. 159) | ||

| Army to Launch Satellite? | Wasn't It von Braun? | |||

| Thursday

6 June 1957 |

• | The U.S. Army, encouraged by the successful firing of its Jupiter guided missile a week ago, was eager to get into the launch of Earth satellite. A top scientist said that Army had created a special type of missile that could be used for launching satellite. The scientists, who requested anonymity, said the vehicle had been developed several months ago at the Army’s Ballistic Missiles Agency laboratory at Huntsville, Ala. His remarks suggested the Army was ready and willing to enter the program if the Navy’s efforts lagged. But when asked about this, an Army spokesman said: “We do not have that missile.” (NYT 7 Jun 57) | c | Who could be the unnamed "top scientist"? Coutd it be Wernher von Braun who, on the da Sputnik was launched, argued that the Army was able to launch a satellite within 60 days using a Jupiter C?! -C.L. |

| Army Denies Report | Navy-Army Rivalry | |||

| Friday

7 June 1957 |

• | Wilber Brucker, Secretary of the Army, denied

reports that the U.S. Army was “eager to move into the Earth satellite

program.” In a statement, he deplored such stories because they tended

to foster inter-service strife.

Mr. Brucker said that the Earth satellite program was “already in the capable hands” of the Navy and that the Army did not covet any part of the Navy’s mission. For the Army to move into the satellite program, Mr. Brucker said, “would constitute gross interference with the Navy effort, would involve unnecessary and expensive duplications and would not be tolerated.” (NYT 8 Jun 57 & NYT 10 Oct 57) |

• | The rivalry between Army and Navy could be traced back to at least ten years. As early as 1946, General Curtis LeMay, of the Army Air Forces, was unwilling to endorse a joint Navy-Army satellite program. On the contrary, the general was resentful of Navy invasion into a field "which so obviously to him was the province of the AAF." (Vanguard p. 7) |

| Soviet Dogs To Be Launched? | "Sputnik 2" Announced | |||

| Saturday

8 June 1957 |

• | “Rocket dogs” may take part in the Soviet Union’s experiments in the International Geophysical Year, reported an article published in Literary Gazette. The newspaper sais some dogs had already reached altitude of more than 95 kilometers in rockets, then had parachuted to Earth without harmful effects. (NYT 9 Jun 57) | c | This announcement, coupled with the 24 March photo of Malyshka's "the experience space dog", practically announced the launch of Laika onboard Spthik 2. -C.L. |

| Russian Satellite in a Few Months | ||||

| Monday

10 June 1957 |

• | Prof. Alexander Nesmeyanov, president of the Academy of Sciences, announced in Komsomolskaya Pravda that the Soviet Union would launch its first artificial satellite "within the next few months,” adding that: “Soon, literally within the next few months, our planet will acquired another satellite, a man-made satellite that is.” (NYT 11 Jun 57) | ||

| R-7 Refused to Take-off | ||||

| Monday

10 June 1957 |

• |  The

second launch attempt of an R-7

missile took place on that day. According to the flickering displays, everything

went normally up to the moment the launch button was pushed. Ignition also

occurred. But, suddenly, shutdown, no fire engulfing the missile. The lights

on the display console died out, and the message “Circuit reset” appeared.

Some valve had failed to open or damage had occurred in the circuit. The

second launch attempt of an R-7

missile took place on that day. According to the flickering displays, everything

went normally up to the moment the launch button was pushed. Ignition also

occurred. But, suddenly, shutdown, no fire engulfing the missile. The lights

on the display console died out, and the message “Circuit reset” appeared.

Some valve had failed to open or damage had occurred in the circuit.

Korolev decided to attempt another try. Members of the launch crew had to run to the missile and change the igniters and others had to set the launch system in the initial state. A little more than 2 hours later, everything was ready for a launch attempt. We had ignition and then the circuit reset again. On a third attempt, the ill-fated valve opened. The missile built up to the preliminary stage and stalled there. The missile was soon engulfed in bright flames lapping in the darkness and then, suddenly, it quickly died out. This happened at midnight between 10 and 11 June. Korolev announced the decision of the technical management: drain the fuel and oxidizer, remove the missile, and return it to the engineering facility. (It was later found that a nitrogen scavenging valve was installed backwards.) (Chertok II p. 358-80; Siddiqi p. 159, Wade 11 Jun 57) |

||

| First Atlas ICBM Tested |

|

|||

| Tuesday

11 June 1957 |

• | The first Atlas intercontinental ballistic missile exploded in flight soon after take-off. Onlookers said the missile began wobbling off course almost immediately after take-off. Thousands of spectators saw a bright flash of orange flame as the missile streaked from its launching site and rose straight upwards. There was an explosion in the sky, and something crashed into the sea. Although the Air Force did not identify the missile as an Atlas, reliable sources said it was the 8,000-kilometers-range missile. (NYT 12 Jun 57) | • | First test flight of prototype Atlas

A was detonated by command signal at 3 kilometers altitude following a

failure in the booster fuel system. The 23-second flight was considered

a partial success. (Wade 11 Jun

57, A&A 1915-60 p. 86)

|

| Evidence Life On Mars | ||||

| Tuesday

18 June 1957 |

• | "Very strong evidence" that a form of life

might exist on Mars was reported

at a joint meeting of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific and the International

Mars Committee. Analyses of light emanating from Mars pointed to the existence

of chemicals characteristic of vegetation. This tended to corroborate

previous visual observations of apparent seasonal changes on the planet’s

surface.

In further support of the vegetation theory, the Air Force reported that it had demonstrated tentatively In the laboratory that some sorts of life known on Earth could survived in the rigorous environment of Mars. The suggestions of vegetative evidence was challenged by some scientist. (NYT 19 Jun 57) |

||

| Soviet to Launch Satellite In 1958 | ||||

| Wednesday

19 June 1957 |

• | Soviet scientists said that they would launch before the end of 1958 the first of a series of artificial satellites. They suggested their crafts would be superior to the United States’ satellite but insisted they had no desire to compete with Americans for the first launching. Yevgeny Fedorov, chairman of the Geophysical Year committee for rocket and satellite research, said no definite or even approximate date for the satellite’s launching could be given. “Russian researchers", he reported, still were facing “many difficulties” but he expressed confidence that these would be overcome. (NYT 20 Jun 57) | ||

| Eigineers Consider Spaceflight | ||||

| Thursday

20 June 1957 |

• | Two NACA groups focused their efforts on the problems involved in manned space flight. One group concerned themselves with performance of aircraft at high speeds and altitudes and with rocket research; the other group, with problems associated with hypersonic flight and reentry. (Mercury C Part 1) | ||

| Soviet Satellite in Few Months | ||||

| Friday

21 June 1957 |

• | The Soviet Union plans to send satellites around the Earth in the next few months from a site approximately in the center of the Soviet Union. The Soviet plans were set out in a document sent on 10 June by I. P. Bardin, vice-president of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, to Lloyd Berkner of the United States. The Soviet document states that the satellites will be used for geophysical, physical and astrophysical experiments in various combinations, and for observations of the relativity theory effect, the study of the shape of the Earth and other investigations. (NYT 23 Jun 57) | ||

| Another Jupiter Missile Test | ||||

| Monday

26 June 1957 |

• | A Jupiter A was launched from Cape Canaveral to test performance of the inertial guidance system, angle-of-attack meters, separation of explosive screws, and impact and radar fusing systems. The flight was successful. Actual range was 250 kilometers, 778 meters over and 389 meters left of the intended impact point. (Wade 26 Jun 57) | ||

| And Soon Moon, Mars and Venus | ||||

| Monday

26 June 1957 |

• | U. S. Khlebtsevich, chairman of a technical committee in charge of radio and television guidance of spacecraft, predicted that this nation would send the first radio guided probe to the Moon in the early 1960s. Within five of ten years, he said, scientists will establish on the Moon a permanent scientific station manned by human beings. He predicted further that an unmanned roving laboratory would be sent to Mars between 1965 and 1971 and that five rockets would be sent to observe the planet Venus. Mr. Khlebtsevich also expressed confidence that the Moscow television center would “very soon” use the Moon to relay its broadcasts to “half the world.” (NYT 27 Jun 57) | ||

| Project Far Side Prepared | ||||

| Wenesday

28 June 1957 |

First phase of Project Far Side was completed, with the lifting by the world’s largest balloon of a load of over a ton of military equipment and instrument to a height of nearly 32 kilometers. (A&A 1915-60 p. 86) |

| July: IGY, the First Step of the Space Age |

| . | July marks the beginning of the 18-month scientific investigation of Earth and space environment, which gave the impetus to the United States and to the Soviet Union to prepared themselve to launch satellites. As reported in the New York Times (below), the feeling at the time was that we were at the “beginning of a new era” as Soviets and Americans were nearly ready to explore space. | ||

| Date | What We Knew Then | What We Now Know | ||

| The Beginning of an Era | ||||

| Monday

1 July 1957 |

• | This day marks the beginning of the International

Geophysical Year (IGY). The scientists

of 67 nations were to participate in a cooperative, world-wide scientific

program. During the next eighteen months, several thousand scientists,

manning stations in all the major nations, on remote islands and polar

ice, will seek to expand knowledge in eleven science fields. And some time

in the spring of next year, man will hurl an artificial moon into outer

space. If the effort succeeds, as scientists believe it will, it will mark

the realization of one of man's most ambitious dreams, and the beginning

of a new era in his history —

possibly the greatest of all eras since his arrival on this planet less

than a million years ago.

The satellite program, according to Joseph Kaplan, chairman of the United States National Committee for the I.G.Y., “represents a new departure in man’s continuing effort to increase his knowledge about the physical universe. Its significance for science, in permitting man to reach into the upper atmosphere to gather data needed for an understanding of his environment, cannot be over-stressed. It is one of the boldest, most imaginative steps taken by man and it represents the first stage in his acquisition of direct knowledge of the universe far beyond the Earth’s surface and far beyond the scope of aircraft, balloons and even conventional research rockets.” The United States satellite program, carried out by the Naval Research Laboratory, calls for the launching of six satellites into space as part of its participation in the I.G.Y. Each satellite will be designed to obtain specific types of information about the nature of outer space. The Soviet Union also plans to launch satellites. It is certain that nature will provide many answers to the vital questions to be put to her. It is even possible that we are on the eve of the discovery of new, hitherto hidden, forces of nature that may make the discovery of atomic energy rather minor by comparison, from the point of view of potentialities for the future of man. But probably most important of all, man’s first venture into the realms of outer space will definitely mark the beginning of the age of interplanetary travel and the conquest of space. (NYT 30 Jun 57, A&A 1915-60 p. 86) |

||

| 165 Successful Missions | ||||

| Monday

1 July 1957 |

• | The Aerobee sounding rocket, used for upper air research, completed 165 successful firings to date. It was first fired on 25 September 1947. (Wade 1 Jul 57) | ||

| Origins of Zenit Spy Sat | ||||

| Tuesday

2 July 1957 |

• | Mikhail Tikhonravov, the first Soviet spacecraft designer, defined the development tasks for the Zenit reconnaissance satellite, which included development of a three-stage version of the R-7, development of satellite guidance and control systems of the precision required for photography from orbit, satellite control equipment, electronic intelligence sensors, guidance systems, film cassette return systems, and tracking systems for recovery of the re-entry vehicle with the film cassette. (Wade 2 Jul 57) | ||

| A Third R-7 Prepared | ||||

| Sunday

7 July 1957 |

• | After an in-depth investigation of the second R-7 trouble, the rocket was hauled out of the MIK assembly building to the launch site. (Chertok II p. 361, Siddiqi p. 160) | ||

| Project Far Side Announced | ||||

| Thursday

11 July 1957 |

• | The Air Force planned to launch a rocket from a sky-platform — a helium-filled balloon that will float at more than 30 kilometers above the Earth —, in an attempt to send a missile thousands of kilometers higher than any rocket yet fired. A spokesman said the rocket was expected to travel “many, many” times higher than the 800 kilometers rockets have attained so far. The Air Force said the test would be made during the summer. These tests would enable scientists to investigate various phenomena at “extreme altitude,” such as cosmic rays and Earth’s magnetic field. (NYT 12 Jul 57) | ||

| Third R-7 Launch | ||||

| Friday

12 July 1957 |

• |  The

R-7

missile finally lifted off to the cheers of observers. At first, the flame

engulfs the missile over the strap-on boosters from top to bottom. One

begins to fear for it; it seems the tanks will explode now, destroying

the launch complex and burning it down. But the plume cautiously lifts

the 300-tons rocket. But soon the euphoria evaporated when, at 33 seconds,

all four strap-ons spuriously separated from the core because of a rapid

rotation around the longitudinal axis. The missile was destroyed. The

R-7

missile finally lifted off to the cheers of observers. At first, the flame

engulfs the missile over the strap-on boosters from top to bottom. One

begins to fear for it; it seems the tanks will explode now, destroying

the launch complex and burning it down. But the plume cautiously lifts

the 300-tons rocket. But soon the euphoria evaporated when, at 33 seconds,

all four strap-ons spuriously separated from the core because of a rapid

rotation around the longitudinal axis. The missile was destroyed.

Following this third R-7 failures, there were some people gossiping behind Korolev’s back about the missile being conceptually flawed on the premise that the 32 parallel rocket combustion chambers could never be made to operate simultaneously and reliably. (Siddiqi p. 160, Chertok II p. 362-3) |

||

| A Jupiter Testflight | ||||

| Friday

12 July 1957 |

• | The flight of a Jupiter A missile, to test the accuracy of the guidance, was successful. The missile followed the predicted trajectory very closely. Actual range was 241 kilometers; survey of the impact crater indicated a miss distance of 50 meters over and 284 meters to the left of the predicted impact point. (Wade 12 Jul 57) | ||

| Russia Behind U.S. in Missiles | ||||

| Saturday

13 July 1957 |

• | According to information accepted in Washington as authoritative, the Soviet Union is substantially behind the United States in the development of intercontinental and intermediate-range ballistic missiles. (NYT 14 Jul 57) | ||

| Signal Bounced From the Moon | ||||

| Saturday

13 July1957 |

• | Signals transmitted by powerful radar equipment of the Army Signal Corps at Fort Monmouth, N.J., and reflected by the surface of the Moon, have been received by one of the Vanguard satellite tracking stations. (NYT 14 Jul 57) | ||

| Soviet to Surprise U.S. | ||||

| Mid-July 1957 | • | Sergei

Korolev had serious meetings with nuclear physicists in Moscow. They

were proposing a new warhead for the R-7 missile with a slightly reduced

yield but almost two times lighter than the existing one. This would instantly

increase our missiles range by

about 4,000 kilometers, to 12,000 kilometers. “We will be able to reach

the Americans from any spot on our territory!” said Korolev with animation.

Also during his visit, Korolev insists on allocating two R-7 rockets for the orbital insertion of artificial satellites. The Americans had announced that they were preparing such a sensation to commemorate the International Geophysical Year (IGY). "If they got the jump on us," wrote Chertok, "this would be a severe blow to our prestige." (Chertok II p. 364-5) |

||

| The Fourth R-7 Prepared | ||||

| Saturday

20 July 1957 |

• | At Baikonur Cosmodrome, boosters of R-7

missile No. 7 were unloaded and arranged at the work stations. This 7 missile

was nicknamed the “Sedmaya semyorka” — the seventh seven or the seventh

Semiorka — and spent a month preparing it at the engineering facility.

According to the schedules, preparation of the missile at the engineering facility would be completed on 12 August — if there were no incidents. Considering the heat and any possible unforeseen circumstances, we decided to add three days and declare 15 August the date the missile would be hauled out to the launch site. If you figured in another 5 days at the launch site, the launch could take place on 20 August. (Chertok II p. 360, 366, 369) |

||

| U.S. Propose to Ban Missiles | ||||

| Thursday

25 July 1957 |

• | The United States proposed to the United Nations Disarmament Subcommittee that an international committee be established to fix the terms of a ban on the military use of intercontinental missiles. Harold Stassen, chief U.S. representative to the five-power group (which included the Soviet Union, Britain, France and Canada), said a board of technical experts on missiles should be set up at part of a first-step arms reduction pact three months after the agreement had become effective. Its task would be to design a system that would insure that outer-space rockets would be used for peaceful purpose only. The United States wants to restrict the use of long-range missiles to purely scientific purposes, as the Soviet proposed a complete ban on the use of all nuclear weapons. Mr. Stassen warned that an uncontrolled race through the outer space in years to come could lead to a great tragedy for mankind. (NYT 26 Jul 57) | ||

| Jupiter A Testflight | ||||

| Friday

26 July 1957 |

• | A Jupiter flight was successful. (NYT 27 Jul 57) | • | The primary Jupiter A test objective was to test warhead and fuse functioning as a system. Actual range was 234 kilometers; survey of the warhead impact point indicated a miss distance of 147 meters short, 182 meters to the left of the predicted impact point. (Wade 26 Jul 57) |

| Manned Spaceflight Possible | ||||

| Monday

29 July 1957 |

• | the Ad Hoc Committee of the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board heard presentations from the Ballistic Missile Division on ballistic missiles for Earth-orbital and lunar flights, and from Air Research and Development Command Headquarters on the two advanced flight systems then under study. Brigadier General Don Flickinger, ARDC's Director of Human Factors, stated that from a medical standpoint, sufficient knowledge and expertise already existed to support a manned space venture. (Mercury O p. 70) | ||

| U.S. Plans to Launch Tiny Satellites | ||||

| Thursday

31 July 1957 |

• | The United States plans to fire a miniature satellite into space some time this fall, as part of the testing of the Vanguard rockets. This will be months in advance of the scheduled program for launching larger satellites. The expectation is that the tiny test satellite will be fired during November. Officials said the small test satellite will be only 16 centimeters in diameter and weight only two kilograms. In contrast to the first scientific satellites, it will not be fully instrumented to record the mysteries of outer space. Officials said they will have a radio transmitter and perhaps an instrument to record temperatures. They still will permit some important scientific observations. The radio transmitter will allow the satellite to be tracked by ground stations, thus providing information on the density of space and on the shape of the Earth. (NYT 31 Jul 57) | ||

| U.S. Developing Nuclear Rocket | ||||

| Tuesday

31 July 1957 |

• | The Atomic Energy Commission said it was developing nuclear power plants that could propel long-range rockets and possibly space ships. (NYT 1 Aug 57) | ||

| Origins of the Scout launch vehicle | ||||

| During

July 1957 |

• | A study was initiated by the Langley Aeronautical Laboratory on the use of solid-fuel upper stages to achieve a payload orbit with as simple a launch vehicle as possible. (A&A 1915-60 p. 86) | ||

| Vanguard TV-2 Troubles | ||||

| Mid-summer 1957 | • | In the summer of 1957 began the long struggle to get the bugs out of Vanguard TV-2. The extensiveness of these bugs came to light early in the summer during the vertical interference and acceptance tests of the vehicle at the Martin plant. Some of the structural discrepancies uncovered at that time gave only minimal trouble, the company coming up quickly with remedies satisfactory to NRL. More serious was the failure of the roll jet and pressurization systems to perform in accordance with specifications. To some extent, these had to be redesigned. Since this was a time-consuming job and time was of the essence, Martin asked the Laboratory for permission to ship TV-2 to Cape Canaveral where the field crew could begin receiving inspections in the hangar while GLM redeveloped the faulty systems. Reluctantly the Laboratory acceded to this suggestion. (Vanguard p. 177-8) | ||

| A 17 September Launch? | ||||

| Summer 1957 | • | Sergei Korolev, Valentin Glushko and the other chief designers had informally targeted the first satellite launch for the 100th anniversary of Konstantin Tsiolkovskiy's birth on 17 September. But achieving this date proved increasingly unrealistic. (Siddiqi p. 165) | ||

| U.S. Knew of Baikonur | ||||

| Summer 1957 | • |

Strangely enough, if U.S. were able to photograph the launch pad, they were never able to catch a R-7 on it. The world had to finally wait until 1967 Le Bourget Aeospace Salon to discover the famous Soviet rocket that launched so many spacecraft. (Photo source: CIA in Chertok iii p. 6; comments: C.L.) |

||

| Mercury Design | ||||

| Summer 1957 | • | Alfred J. Eggers, Jr., of the NACA Ames Aeronautical Laboratory, worked out a semiballistic design for a manned reentry spacecraft. (Mercury C Part 1) |

| August: The "Ultimate Weapon" Is Here |

| . | In August, the Soviet R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) flew successfully for the first time. This event, although it occurred in secret, changed forever our history. As the ultimate weapon of the Cold War, it made possible to destroy any city around the world with nuclear warheads. However, the R-7 also became the most used space launch vehicle: the Sputnik’s, Vostok’s and Soyuz’ launcher which orbited thousands of spacecraft (including today’s cosmonauts). When announced by the Soviets, this success also baffled the Americans, who were considering themselves the undisputed leader in weapon technology. | ||

| Date | What We Knew Then | What We Now Know | ||||

| Vanguard Needs More Money | ||||||

| Friday

2 August 1957 |

• | The U.S. Navy has asked Congress to appropriate $34.2 millions to complete the Vanguard satellite program. (NYT 3 Aug 57 & 5 Aug 57) | ||||

| Soviet Confident to Launch Satellites | ||||||

| Saturday

3 August 1957 |

• | Professor Evgenii Fyedorov, who had been officially named head of the Russian satellite program, say that the launching of a Soviet satellite during the year “is a stepping stone — and an important one — to space travel by cosmic ships.” The Soviet academician told foreign newsmen In Moscow recently: “No date can be given for launching our satellite, but it will be launched at the most profitable moment for science. Different satellites will have different weights,“ he added. The first satellite would be launched at dawn atop a three-stage rocket, he said. (NYT 4 Aug 57) | ||||

| Earth Magnetic Field Measure | ||||||

| Tuesday

6 August 1957 |

• | A team of scientists led by L. Cubill and J.A. Van Allen made first measurements of the terrestrial magnetic fields in the auroral zone with the firing of State University of Iowa’s Rockoon No. 50. (A&A 1915-60 p. 87) | ||||

| Important Accomplishment for Jupiter | Thinking About Satelite | |||||

| Wednesday

7 August 1957 |

• | A U.S. Army-JPL Jupiter C test missile, with a scale-model nose cone, was fired some 2,000 kilometers down to Cape Canaveral. Its nose cone reached a peak altitude of over 950 kilometers. Recovered the next day, the nose cone proved conclusively that the planned ablative heat protection for Jupiter warheads was satisfactory. The nose cone contained a letter addressed to Maj. Gen. John Medaris, commander of the Army Ballistic Missiles Agency at Huntsville. Ala. The letter contained this message: “If you get this letter, it will be the first letter delivered by missile.” (This nose cone was displayed by President Eisenhower to a nation-wide television audience on 7 November). (A&A 1915-60 p. 87, Mercury C Part 1, Wade 8 Aug 57, NYT 8 Nov 57) | • | Late in 1956, the Department of Defense authorized ABMA to develop and fire twelve Jupiter Cs as part of the Army's nosecone reentry development program. The first two shots were failures, but a third, fired in August. was such a definitive success that General Medaris, the ABMA commandant, ordered the reentry test program stopped and directed that the remaining Jupiter Cs — "nine precious missiles" — be "held for other and more spectacular purposes." By "other and more spectacular purposes," the dynamic ABMA chief meant a satellite launch. (Vanguard p. 200) | ||

| Did an Object Escaped Earth? | ||||||

| Saturday

10 August 1957 |

• | In the summer of 1957, physicist Bob Brownlee attempted to “contain” the blast effects of an atomic explosion from a device placed at the bottom of a 150 meters vertical shaft in the Nevada desert. A 10-centimetres steel plate weighing several hundred kilograms was placed over the hole. This blew off as expected in the blast and was seen in films to depart the area at six times the escape velocity. This is possibly the first man-made object ever to escape from Earth. (Wade 10 Aug 1957) | ||||

| Army Ready to Launcyh a Satellite | ||||||

| Mid-August 1957 | • | Shortly after the successful Jupiter C

reentry test in the summer of 1957, Major General John Medaris, commander

of Army Ballistic Missile Agency at Redstone Arsenal, wrote Lieutenant

General James Gavin, then Chief of Research and Development for the Army,

that "we could hold two of the missiles in such condition that one satellite

shot could be attempted on four months' notice, and a second one a month

later."

Medaris confesses that he was convinced that Project Vanguard's chance of effecting an orbit in the IGY was "so small as to constitute a ridiculous gamble." (Vanguard p. 200) |

||||

| The first "Space Man" | High-altitude Manned Flight | |||||

| Monday-Tuesday

19-20 August 1957 |

• | Airborne for 32 hours in Man High II flight, USAF Maj. David Simons established a manned-balloon altitude record of 31 kilometers. On 22 August, the New York Times published an editorial titled: “The First Space Man.” (A&A 1915-60 p. 87, NYT 20 Aug 57, 21 Aug 57, 22 Aug 57) | • | The Manhigh II balloon reached a record altitude of 30,950 meters with Major David Simons aboard on 19 and 20 August. Including the pilot and scientific equipment, the total weight of the Manhigh II gondola was 747 kg. (Wade 19 Aug 57) | ||

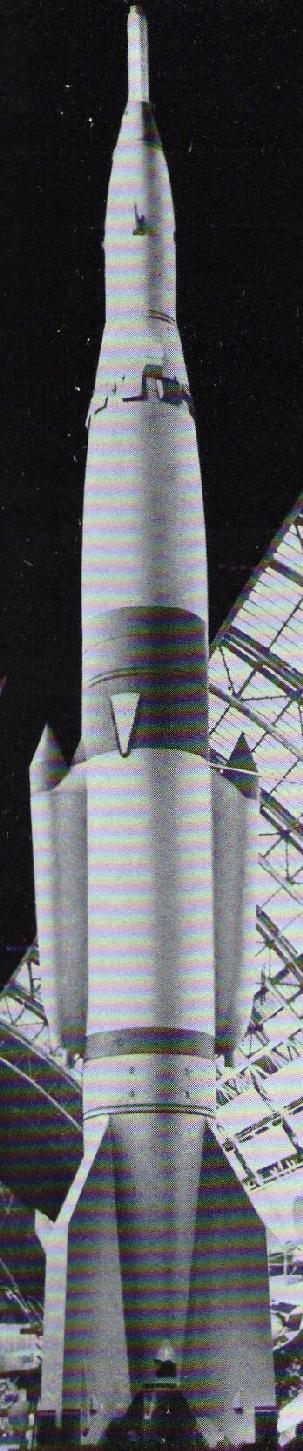

| The First ICBM Successful Flight | ||||||

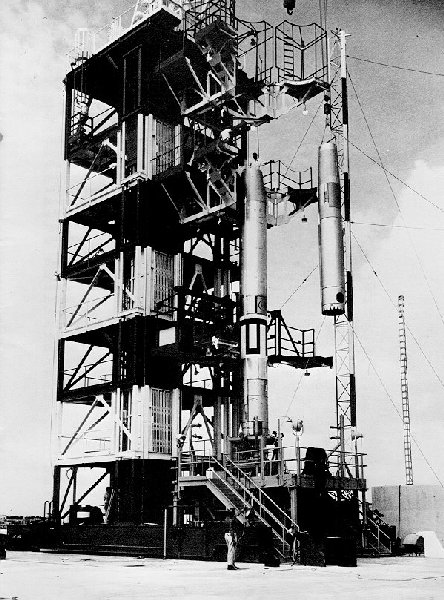

| Wednesday

21 August 1957 |

An original R-7 ICBM at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in 1957. |

• | The fourth R-7

successfully lifted off from its launch pad at 18h15, Baikonur Time. The

missile flew 6,500 kilometers and its warhead entered the atmosphere over

the target point at Kamchatka. The only damper on the mission came when

the specially constructed heat shield for the dummy warhead disintegrated

at an altitude of ten kilometers because of excessive thermodynamic forces.

A quickly dispatched search party spent almost a week gathering the remains

of the dummy warhead and its thermal coating.

Chertok explained: “By all appearances, the nose cone had burned up and dispersed in the dense atmospheric layers quite close to Earth. It wasn’t so easy to select a new configuration for the nose cone. Quite a bit of time would be required for wind tunnel tests and fabrication. What were we supposed to do now? Stop testing? “To be honest, we did have a missile, but we did not yet have a hydrogen bomb carrier: who would entrust such a payload to us, if the payload container disintegrated and burned up long before it hit the ground.” (Siddiqi p. 160-1, Chertok II p. 372 |

|||

| New Troubles for Vanguard | The “Truth” About Vanguard | |||||

| Thursday

22 August 1957 |

• | Vanguard TV-2’s

prelaunch preparations reach the point where the crew at the pad could

attempt a static firing. After lengthy delays during the countdown, during

the first attempt to pressurize the fuel tanks, a liquid oxygen vent failed

to relieve excessive pressure. When the vent refused to close fully during

several succeeding attempts, the static firing was scrubbed.

The second static test, attempted four days later, encountered even worse luck than the first. Among other things, the blast deflector tube of the firing structure suffered serious damage. The firing was report to another week. (Vanguard p. 180, 181-2) |

• | Today former Vanguard men can say calmly that the nightmare of TV-2 was "just one of those things." Back in the Vanguard days, Jim Bridger has commented: “We were aware that the ultimate source of our funds, the Department of Defense, had reservations about the value of a purely scientific missile development. Consequently, we made political fodder out of saying the Vanguard vehicle was just an outgrowth of the Viking research rocket. Frankly, that was an exaggeration… for all practical purposes the Vanguard vehicle was new, new from stem to stem. More to the point, it was an awfully high state of the art vehicle, especially the second-stage rocket.” (Vanguard p. 177) | ||

| Vanguard Gets New Money | ||||||

| Saturday

24 August 1957 |

• | The U.S. Congress appropriated $34.2 million

to the U.S. Navy Vanguard scientific

satellite program. (A&A 1915-60

p. 87)

(On 9 October, President Eisenhower said the first estimate of the cost of the Vanguard program was $22 millions, that this went to $66 millions and than to $110 million, “with notice that that might have to go up even still more.”) (NYT 10 Oct 57) |

||||

| Soviet Biological Flights | ||||||

| Sunday

25 August 1957 Saturday 31 August 1957 |

• | At the end of August, the Soviets proceed with two high-altitude biological flights using R-2A missiles (No. 3 and 4) which flew respectively up to 206 and 185 kilometers. (Wade 25 Aug 57 & 31 Aug 57) | ||||

| Soviet Announced Their Success | Announcement Impacts | |||||

| Monday

26 August 1957 |

• | Shortly before midnight, the Soviet Tass

news agency reported:

“But the Soviet announcement about the missile was significantly linked with a disclosure that the Government also had successfully tested in recent days 'a series of nuclear and thermonuclear (hydrogen) weapons.' At least one of these tests, also In the Soviet interior, was recorded in the United States and was believed to have taken place last Thursday." (NYT 27 Aug 57) |

• | It was extremely unusual for Soviet authorities

to publicize successes in any military field, and this particular anomaly

can perhaps be explained by the fact that the press release was aimed as

much at the United States as it was at Khrushchev's own opponents after

the dangerous "Anti-Party Group" had nearly wrested power from him during

the summer of 1957.

Clearly, the communiqué did not have the intended effect on the U.S. public or media, because, for the most part, little attention was given to it. Those who did pay attention spoke only to dismiss the claim: a stance justified partly by the black hole of information on Soviet ballistic missiles in the open press. It would take thirty-eight more days before the entire world would take notice that a new age had arrived, heralded by that same ICBM. (Siddiqi p. 161) What’s more, Right after nose cone separation, it collided with the body of the core booster. "Four launches and still no absolute intercontinental weapon," comment Boris Chertok. "The Tass’ report e was a bluff in the sense that the missile had no warhead. But aside from the very few of us who were privy to the secret results of the flight tests, no one knew." (Chertok II p. 372, 373, 383) |

||

| U.S. Had No Reason to Doubt | ||||||

| Tuesday

27 August 1957 |

• | Secretary of State Jonn Dulles said that

he had no reason to doubt Moscow's statement that it had successfully tested

an

intercontinental ballistic missile. But, he added, he does not think that the military balance of power between East and West will be disturbed by this or other missile developments for some time to come. (NYT 28 Aug 57) |

||||

| Permission to Launch | ||||||

| About 23-27 August | • | At a State Commission meeting soon after the R-7

success, Sergei Korolev

formally asked for permission to launch the first

satellite if a second R-7 successfully flew in early September. Convincing

the commission proved to be much harder than expected — there were individuals

who were not interested in the satellite attempt — and the meeting ended

in fierce arguments and recriminations.

Not easily turned away, Korolev tried again at a second session soon after, this time using a political ploy: "I propose let us put the question of national priority in launching the world's first artificial Earth satellite to the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. let them settle it."' It worked. None of the members wanted to take the blame for a potential miscalculation, and Korolev got what he wanted. (Siddiqi p. 164-5) |

||||

| U.S. Missile Launched | ||||||

| Wednesday

28 August 1957 |

• | An intermediate-range guided missile was fired from the Air Force Florida's test center in the wake of Russian claims of having perfected an intercontinental ballistic missile capable of delivering an atomic warhead anywhere in the world. (NYT 29 Aug 57) | • | The fourth Jupiter was fired from Cape Canaveral and was the second successful flight of the series. All flight missions were fulfilled satisfactorily. (Wade 28 Aug 57) | ||

| Pentagon on Soviet ICBM | The Real Count | |||||

| Friday

30 August 1957 |

• | Department of Defense announced that four to six Soviet ICBM tests took place in the spring of 1957. (A&A 1915-60 p. 87) | • | Including launch aborts, the four R-7 missiles attempts were on 15 May (in-flight failure), 11 June (launch abort), 12 July (in-flight failure) and 21 August (success). There were also two additional attempts on 10 June, both of which were aborted just before ignition. (Chertok II p. 371) | ||

| Missile Test | ||||||

| Friday

30 August 1957 |

• | A Thor missile failed to lift-off from Cape Canaveral. (Wade 30 Aug 57) | ||||

| A Spherical Shining Satellite | ||||||

| Saturday

31 August 1957 |

• | According to a Moscow radio report, a scientific lecturer explained that Soviet Union soon would launch two types of Earth satellites, one of which would be a hollow aluminum sphere, 65 centimeters in diameter and weighing ten kilograms, carrying instruments to send back data. The other would carry no instruments. “This type of satellite will be observed through telescopes and will make it possible to determine the precise shape of the globe and its irregularities,” the lecturer said. “It will be called the ‘Beacon’ and will probably look brighter than a star of first magnitude.” (NYT 1 Sep 57) | ||||

| Washington’s Conference on Rockets and Satellite | The "Sputnik" Conference | |||||

| Saturday