|

|

|

Dernière mise à jour : 15 mars

2003

.

•

Données

techniques

•

Données

techniques

•

L'équipage

•

Présentation

de la mission

•

Compte-rendu

de la mission

Première semaine suivant

la destruction de Columbia :

• 1er février

: « Il est beaucoup trop tôt

pour savoir… »

• 1er février

: Ce que la NASA nous dit

• 2 février

: Gare aux faux-experts !

• 2 février

: Columbia victime de « circonstances

exceptionnelles » ?

• 2 février

: Ce que nous dit la NASA

• 2 février

: Que sera l'après-Columbia ?

(article publié dans La Presse)

• 3 février

: « Challenger : c’est

reparti ! »

• 3 février

: À la recherche du «

chaînon manquant »

• 3 février

: Les derniers instants de

Columbia

• 4 février

: L’enquête fait des

« progrès considérables »

• 5 février

: « Je vous l’avais bien dit

! »

• 5 février

: « Vous faites fausse route

! »

• 5 février

: Columbia « frappé

» dans le ciel californien ?

• 6 février

: Au sujet des causes possibles

de l’accident

• 7 février

: Des observations intéressantes,

mais il faut attendre

• 7 février

: Première semaine frustrante

d’une longue et difficile enquête

Deuxième semaine suivant

la destruction de Columbia :

• Commentaire

: Nous leur devons bien la Vérité…

• 10 février

: Ce que nous dit la NASA (en anglais)

• 11 février

: « Notre mandat : trouver

la cause de l’accident »

• 11 février

: Ce que le CAIB nous dit (en anglais)

• 13 février

: Communiqué spécial du

CAIB (en anglais)

• 13 février

: Les restes des astronautes récupérés

(en anglais)

• 13 février

: Ce que le CAIB nous dit (en anglais)

• 13 février

: Le tracé des derniers

moments de Columbia

• 14

février : Le déroulement

du drame

Troisième semaine suivant

la destruction de Columbia :

• 15 février

: Ce que nous dit la NASA (en anglais)

• 18

février : Ce que nous dit la NASA

(en anglais)

• 18 février

: À la recherche de la «pierre

philosophale»

• 20

février : Ce que la NASA nous dit

(en anglais)

• 20

février : Ce que nous dit le CAIB

(en anglais)

• 21

février : Cartes des derniers moments

de Columbia

Quatrième semaine suivant

la destruction de Columbia :

• Perspectives

:

Columbia a-t-il été

victime de son aile gauche ?

• 24

février : Ce que la NASA nous dit

• 24

février : Aurait-on pu observer

des dommages sur l’aile gauche ?

• 24

février : Columbia observé

depuis la Terre

• 25

février : La NASA a-t-elle bien

évalué les risques que courait Columbia?

• 25

février : Ce que pense Sean O'Keefe

des courriels (en anglais)

• 25

février : Ce que la NASA nous dit

(en anglais)

• 28

février : Le vidéo des

dernières minutes avant l'accident...

• 28

février : À propos du vidéo

des dernières minutes de Columbia

Cinquième semaine suivant

la destruction de Columbia :

• 4 mars

: Que reste-t-il de Columbia... (photos)

• 4 mars

: Ce que la NASA nous dit (en

anglais)

• 7

mars : Nouveaux clichés des restes

de Columbia

Sixième semaine suivant

la destruction de Columbia :

• 8 mars

: Le bord d'attaque de l'aile gauche attaqué par

le plasma ?

• 11 mars

: Ce que les enquêteurs nous disent (en anglais)

• 11 mars

: Triste retour pour Atlantis...

Septième semaine suivant

la destruction de Columbia :

• 15 mars

: Paralysie et crises majeures

..

| Voir aussi : | Les Questions que tout le monde se pose |

| Les courriels des lecteurs | |

| Mes impressions personnelles | |

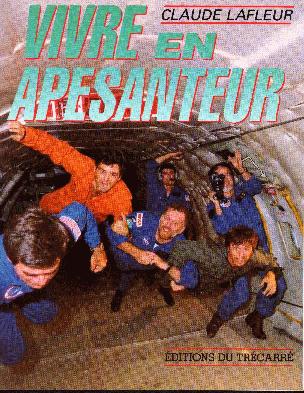

Chapitres

de Vivre en apesanteur (1988) Chapitres

de Vivre en apesanteur (1988)

1 -- À bord de Challenger, ce 28 janvier… 2 -- À l’abris d’une nouvelle catastrophe ? 3 -- Comment parer à toute éventualité |

|

| Site de la NASA consacré à la Destruction

de Columbia

Voir aussi : Status Reports et Transcripts and other Media Resources) |

|

| Report of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident (the «Rogers Commission Report), June 1986. |

10 Mars : plus récente Chronologie

des dermières minutes du vol de Columbia (fichier Excel) publiée

par le CAIB,

.

| Below are some comments made by four of the members of the Columbia

Accident Investigation Board during the weekly press briefing.

Harold Gehman, chairman of the CAIB: "I think that we've had a good

week here. We are moving along methodically in our understanding of what

happened to the orbiter. Let me rephrase that: We're moving along nicely

in our understanding of the forces that were at work on the orbiter as

it failed to properly enter the Earth's atmosphere. I would not want to

say that we're moving along rapidly at finding the cause, because it remains

to be elusive. But we are doing a considerable amount of good hard engineering

and science work at understanding the environment and the forces that the

orbiter was subjected to and also narrowing down the part of the geography

on the orbiter where the assault seems to have taken place.

John Barry: "We have [found] what I would characterize as an interesting aspect on [the Space Shuttle] ascent. At 62 seconds into launch, we saw one of the larger transients we've seen on the solid rocket motor. It was well within parameters but, interestingly enough, the two largest ones we've seen on ascent both happen to be Columbia, both happen to be going on 39 degree inclinations, both have lightweight tanks. So we're trying to identify if there's any commonality there as an additional stress load on the left-hand side of the orbiter, because it was on the left solid rocket motor that had this input. Again, well within parameters, but just one more as we follow the foam, as we follow the transient stresses on the orbiter that might have been able to contribute to one more issue as we trace down this detective story." About possible damage resulting from the "foam" that hit Columbia 80 second into its launch, one expert comments: "What we're really looking at is a complex failure of a complex system. One of the scenarios we're looking at is that it's possible that the foam striking a healthy orbiter would not have done enough damage to cause the loss of this orbiter. But it's possible that foam striking an unhealthy orbiter that had problems in it, either due to stresses on launch -- we talked about the wind sheer, too much heating and recoveries of too much heating and transition of the years before, aging of the orbiter like the RCC faults we see, or a whole number of other complex issues -- it's possible that you could do some damage to this orbiter that would have been as a result of a normal event which she could have survived at age 10, maybe she couldn't survive it at age 21." "Was it foam or ice combination ?", asked a reporter, "Has NASA told you that in their belief that debris contained no ice?" Harold Gehman answered: "I don't know that anybody's been that firm about it yet. I think that that's still an open question as to whether or not there might be ice in there or not." On the piece floating out of Columbia on the second day of the flight, John Barry comments: "It is not unusual, by the way, to have this happen. Ice has come off. We have had reports from astronauts that screws and washers, even parts of blankets when the orbiter doors are opened, for some things to fly out in there. The question now is, with all the seriousness and obviously with the mishap, was that something that was off the left wing that subsequently was damaged on ascent. So it obviously has a heightened awareness. And it wasn't cited by any of the astronauts reported by in communications. So we have to go back to the detective story of trying to figure out what it is on radar signatures that might help us find out what that is." A reporter asks how long will it take to know what went wrong: “I mean,

he added, the space station is up there and the clock is ticking on getting

the shuttles back in flight.” Harold Gehman answered: "But if we don't

know anything, we can't say anything. So, we can't possibly work any harder

than we are; we're already working seven days a week. Now, the energy level's

still very high, both among the debris pickers, the debris analysts and

this board, and I would not want to put any kind of time frame on it."

Voir les photos (techniques) accompagnant la présentation du CAIB |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Un

mois et demi d’enquête n’a toujours pas permis d’identifier les causes

de la disparition de Columbia le 1er février dernier.

Lors

de son plus récent point de presse, Harold Gehman, le chef des enquêteurs,

a tout bonnement admis être encore loin d’avoir cerné les

origines de la tragédie. «Nous comprenons de mieux en mieux

l’environnement et les forces auxquelles a été soumis Columbia,

a-t-il déclaré. Mais je ne dirais pas que nous progressons

rapidement quant à trouver les causes, celles-ci demeurant obscures.

» L’amiral Gehman a même évoqué que les

conclusions de son enquête pourraient n’être publiées

qu’à l’été.

Or,

voilà qui rive au sol les Navette et qui menace même la Station

spatiale internationale ISS. En effet, tant qu’on n’aura pas cerné

les causes de la tragédie, les deux grands volets du programme spatial

américain se trouvent paralysés.

Il

est notamment impossible de prendre quelque mesure que ce soit en prévision

de l’éventuelle reprise des vols de Navette. Les enquêteurs

ont en effet ordonné la suspension de tous les travaux reliés

aux navettes – dont l’entretien des orbiteurs et la fabrication de nouvelles

composantes – afin de pouvoir scruter l’état du programme tel qu’il

était au moment du drame. De surcroît, faute de savoir, les

spécialistes de la NASA ne peuvent envisager des solutions pour

remédier à ce qui a pu entraîner la perte de Columbia.

Bref, c’est la paralysie totale.

| 8:51:19 | Twenty-six seconds after the start of peak reentry heating just off the California coast at Mach 24, "remote sensors indicate off-nominal external event -- earliest known event." The reference to "remote sensors" is indicative of U.S. military aircraft, ground- or space-based sensors. Space-based assets include DSP missile warning satellites or a Cobra Brass "staring array" developmental missile warning sensor on a National Reconnaissance Office spacecraft. |

| 8:51:46 | Inertial sideslip goes and stays negative, indicating rolling/yawing torque. |

| 8:52:05 | First clear indication of "off-nominal aero increments" in yaw. Abnormal telemetry begins and continues for next 8 min. to breakup. |

| 8:52:32 | Water dump nozzle on left fuselage shows temperature rise. The meaning of this intriguing data is unknown. |

| 8:53:01 | First clear off-nominal roll moments. |

| 8:53:44 | Observers in California see the first of more than a dozen debris separation events. |

| 8:54:33 | First "flash" event where orbiter envelope suddenly brightened. Sixth debris sighting occurs 2 sec. later. |

| 8:55:30 | "Remote sensors" indicate abnormal external event. |

| 8:55:55 | At about Mach 21 and 222,000 ft. over the Utah/Arizona state line, the 13th debris shedding event is observed by people on the ground. This was followed 2 sec. later by "very bright debris" departing the orbiter. |

| 8:58:40 | Tire pressure alarms in cockpit and Mission Control. |

| 8:59:32 | Loss of signal in Mission Control due to orbiter tail/TDRSS blockage. |

| 8:59:33 | Cockpit master alarm sounds for unknown reason. |

| 8:59:35 | Sideslip changes sign. Aerodynamic forces due to sideslip begin reinforcing aerodynamic asymmetry. |

| 8:59:36 | Autopilot drops left wing to compensate for increasing aerodynamic moments, creating bank-attitude error. |

| 8:59:37 | Begins 25-sec. period of no data. |

| 9:00:02 | First large piece of debris (Debris A) departs. |

| 9:00:02 | Start of final 2 sec. of reconstructed data. Data indicate the vehicle was in "an uncommanded attitude" beginning to yaw left at least 20 deg./sec., although this is maximum sensor capability. Flight control mode was in auto. Main fuselage and structure and systems on right side of vehicle, including the right wing, were intact. |

| Systems showing nominal operation included the three auxiliary power units, water spray boiler, fuel cells, forward fuselage avionics and environmental control system. | |

| Off-nominal systems at this time were all three hydraulic systems, left elevon data, flash evaporator and multiple sensor indications in the left Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) pod. | |

| Multiple primary and backup computer system alarms for the left OMS pod were found in computer buffer. Multiple elevated temperatures registered for left side of orbiter. | |

| 9:00:03 | Possible rotational hand controller activation indicating possible attempt by the pilots to select manual control -- although at loss of all telemetry, the vehicle was still on autopilot and the hand controller was secured in its detent. |

| 9:00:17 | "Debris B," large piece separates. |

| 9:00:18 | "Debris C," large piece separates. |

| 9:00:21 | "Vehicle main body breakup." |

14 mars: plus récente chronologie des dernièrs minutes du vol ("Revision 15"), en format .pdf et en format Excel. Tables des abréviations (Source (CAIB)

18 mars : Ce que les enquêteurs nous disent

| ADM. GEHMAN: I literally have almost nothing here to say, very

few announcements to make. [...] The only other announcement

that I have is that we have a number of interim recommendations that are

beginning to percolate up through the staff, through the board. I'm not

ready to announce any right now, but we've always mentioned that when we

came to a conclusion on anything, that we would issue that when we were

confident. And we have a couple of them that are bubbling up and they are

at various stages of maturity. When they're ready, you can expect that

we'll be issuing some interim findings and recommendations.

Steve Wallace, operations and management panel : I want to talk a little bit about the decision-making issue. We've heard an awful lot about E-mails and particularly as regards requests for DOD imaging assets; on again, off again. I think an important thing to say about the E-mail trail is that's certainly not the story. That's maybe a fraction of it. So while we read and organize and storyboard and try to figure out the whole story of what happened specifically and what it says sort of culturally in terms of communication practices and relationships among different parts of the organization, we're heavily involved in witness interviews. We're doing typically several every day and will be for some time. I would also like to say we are trying to be fair about all this and not view this with perfect 20/20 hindsight. Obviously there are a lot of people who, in retrospect, may have wished they had done something differently, whether or not it might have affected the ultimate outcome. We are trying to sort out in all these communications, E-mails, phone calls, whatever, what really constitutes normal banter, normal what-ifing versus something that's keep that in context. General Deal Radar signature testing. I mentioned it's happening right

now at the Air Force research lab at Wright Patterson Air Force Base. We're

doing testing for two purposes. One is for that mysterious object that

we talked about that was seen from Day 2 to Day 4 on orbit of the orbiter,

to try to see what type of radar characteristics we may be able to get

out of this testing if we could perhaps determine what it was that separated

from the shuttle and then reentered a few days later. [...] about

this mysterious object. To remind you, this was discovered after the accident

versus while it was on orbit. This was not something being tracked while

it was on orbit. This was a result of about six days later of what we like

to call the most laborious examination in space command history. If you

think about the orbiter as it's going around the globe, there are 3180

different observations of the shuttle. Now, this was more keeping track

of the shuttle versus tracking the shuttle, 'cause that's not the mission;

we're not tasked to do that in space command. We do track for it and we

do de-conflict it with any known objects in space, but they weren't doing

this fine-tooth examination while it was on orbit. So I just want to make

that point that this was after the accident.

|

..

| Mission STS 107 | Semaine 1 | Semaine 2 | Semaine 3 | Semaine 3 | Semaine 5 |

| ISS Expédition 6 | STS 114 / ISS ULF-1 |

© Claude

Lafleur, 2003