| This spacewalk is one of the most significant

one ever done because it revealed how much it is difficult to work outside

a spacecraft. Up to that day, engineers and ground controllers thought

that spacewalking astronauts could do about anything, but Eugene

Cernan's EVA revealed the opposite: the simplest task needs to be carefully

planned in advance. Cernan nearly lost his life — more than once — during

his spacewalk!

After the troublesome Gemini

8 mission, during which David Scott was to have performed an EVA, Gene

Cernan became the second U.S. spacewalker on this Gemini 9 mission. He

is the first to have made an entire orbit around the world out of a spaceship,

to have sense both day and night in space. In his biography,

Cernan told:

“When I pumped my suit up to three and one

half pounds of pressure per square inch, the suit took on a life of its

own and became so stiff that it didn't want to bend at all. Not at the

elbow, the knee, the waist, or anywhere else. It was as if I wore

a garment made of hardened plaster of Paris, from fingertip to toe.

“When the hatch stood open, I barely pushed

against the floor of the spacecraft and my suit unfolded from the seated

position. I grabbed the edges of the hatch and climbed out of my hole until

I stood on my seat.

“And, oh, my God, what a sight. Nothing had

prepared me for the immense sensual overload. I had poked my head inside

a kaleidoscope, where shapes and colors shifted a thousand times a second.

I did not have the words to match the scene. No one does.

“While Tom [Gemini 9 Commander Tom

Stafford ] held my foot to anchor me, I positioned a sixteen-millimeter

Mauer movie camera on its mount and retrieved a nuclear emulsion package

that recorded radiation data and measured the impact of space dust. Then

I stretched forward and planted a small mirror on the nose of the spacecraft.

Using it, Tom could watch when I started my trek back to the AMU [Astronaut

Maneuvering Unit “space scooter”].

“My only connection with the real world was

through the umbilical cord, which we called the "snake," and it set out

to teach me a lesson in Newton's laws of motion. My slightest move would

affect my entire body, ripple through the umbilical, and jostle the spacecraft.

We were forced into an unwanted game of crack-the-whip, with Tom inside

the Gemini and me on the other end of the snake.

“Since I had nothing to stabilize my movements,

I went out of control, tumbling every which way, and when I reached the

end of the umbilical, I rebounded like a Bungee jumper, and the snake reeled

me in as it tried to resume its original shape. I hadn't even done anything

yet and was already losing the battle. There had been no advance warning

on the difficulties I was having because everything I did was new. I was

already beyond the experiences of White and Leonov,

moving into uncharted territory. Nobody in history had ever done this before.

“I felt as if I was wrestling an octopus.

I was looping crazily around the spacecraft, ass over teakettle, as if

slipping in puddles of space oil, with no control over the direction, position

or movement of my body, and all the while the umbilical was trying to lasso

me. Without a stabilizing device, I had no control over the umbilical,

and it pretty much did whatever it wanted. "I can't get to where I want

to go," I told Tom in exasperation. "The snake is all over me."

“I fought it for about thirty minutes before

deciding that this snake was perhaps the most malicious serpent since the

one Eve met in the Garden of Eden.

“I took a short break before moving to the

rear of the spacecraft, where the backpack was stowed, and again was faced

with the enormity of what lay before my eyes, a feast for the senses.

“I needed to reach the rear of the spacecraft

while I still had sunlight, then check out the backpack and strap it on

during darkness. Then I would exchange the umbilical connected to my chest

pack for the power and oxygen contained within the AMU, and tether myself

to the spacecraft with a 125-foot-long [38 metres] piece of thin nylon

line. So the next time the Sun popped up, Tom would flip a switch, the

single bolt holding the backpack to the Gemini would shear, and I'd be

off, rocketing around on my own, the first human to be an independent satellite.

Master of the Universe.

But first, I had to get to where the backpack

was folded up like some bizarre bird in a nest. My space suit fought my

every move, and I needed both flexibility and mobility, the two things

it did not have. It was blown up like a balloon figure in the Macy's Thanksgiving

parade, and tried to hold that shape, no matter how I sought to bend it.

Push in on a party balloon and it will resume its original shape when your

finger pressure is removed. Same thing in outer space. My heartbeat increased

with the effort, and I was breathing hard, trying to find leverage.

“I worked my way hand-over-hand along a small

railing, we entered darkness over South Africa. I unfolded the restraining

bars alongside the backpack, and clicked on a pair of tiny lights for illumination.

Only one lit up, providing less help than a candle. Lord I was tired. My

heart was motoring at about 155 beats per minute, I was sweating like a

pig, and I had yet to begin my real work.

“I could barely see anything at all as I worked

through the thirty-five different functions required to make the thing

ready to fly. What seemed simple during our Earth simulations was nearly

impossible in true zero gravity. Sweat beaded on me and stung my eyes.

The helmet prevented me from wiping them. Eventually I flipped the final

switch and the backpack powered up. Almost time to fly.

“I was having a hard time seeing things, but

it took a while to realize that it wasn't just because of the darkness.

I was working so hard that the artificial environment created by the space

suit simply could not absorb all of the carbon dioxide and humidity I was

pumping out. Vision through my helmet was as mottled as the inside of a

windshield on a winter morning, and I told Tom, "This visor is sure fogging

up."

“The work was more than hard, and I was panting

for breath as my heartbeat soared to 180 beats per minute. Since the visor

was fogged on the inside, and I obviously couldn't remove the helmet to

wipe it dry, my only choice was to rub my nose against the inside of the

shield to make a hole through which I could see.

“Although my mask was cold, my lower back

was scalding hot. During the somersaults of daylight umbilical dynamics,

I had ripped apart the rear seams on those seven inner layers of heavy

insulation and the Sun had baked the exposed triangle of unprotected skin.

Now I had a major sunburn and nothing could be done about it until I took

off the suit, which would be at least another day. I had a lot bigger things

to worry about at the moment, so I disregarded the fiery sensation.” […] |

|

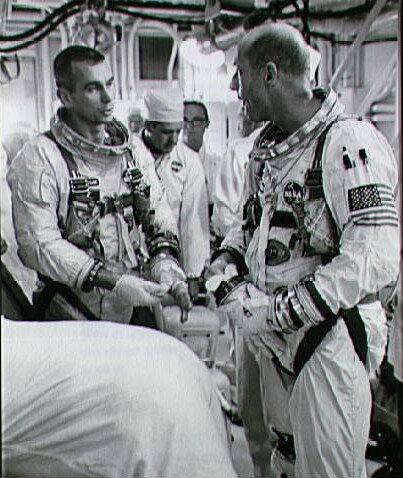

| Gemini 9 Commander Thomas Stafford (left)

and Pilot Eugene Cernan. |

|

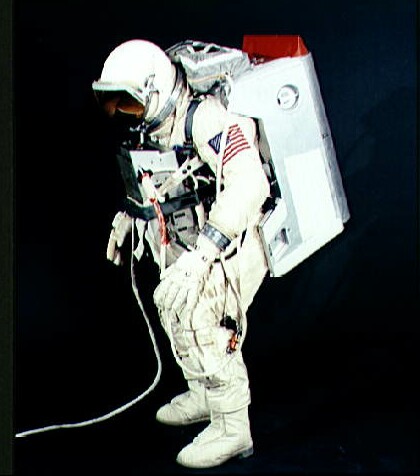

| A spacewalking astronaut with an AMU. |

|

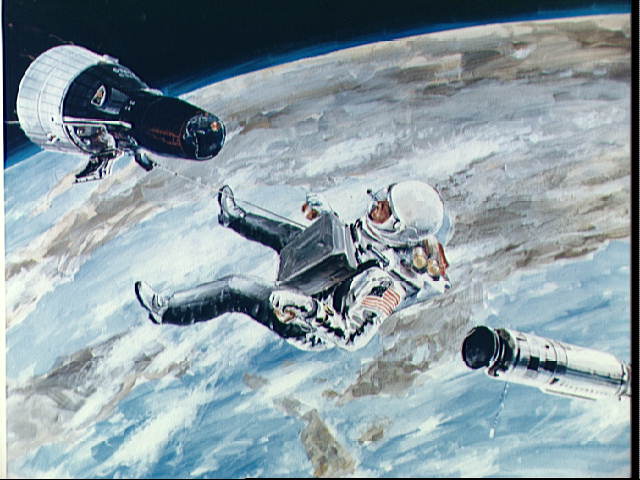

| Artist rendition of the Gemini flight, with

a spacewalk and an Agena dcoking target. |

|

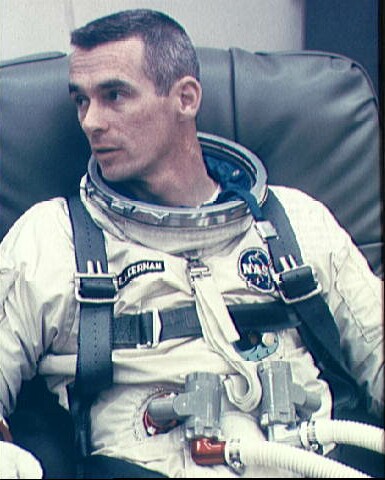

| Cernan in his spacesuit (before the flight). |

|

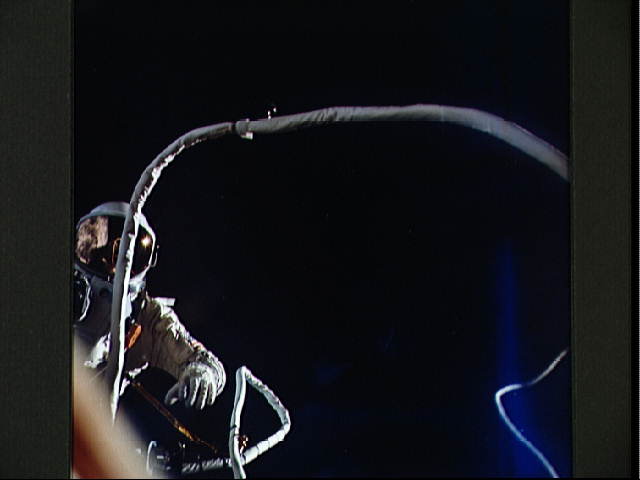

| One of the rare photo of Cernan outside his

spaceship. (There are no good pictures of Cernan's historic EVA because,

at the end of the walk, the camera with which Stafford took pictures fled

out of the spacecraft.) |

|

| Cernan and Stafford before the flight. |

|

|

|